What is the European corn borer?

European corn borer (Ostrinia nubilalis) is a destructive corn pest in Wisconsin and across most major corn-growing areas in the United States. It was introduced to the United States in 1917. The widespread devastation of corn crops led European corn borer to be the first target of Bt corn hybrids in 1996.

Larvae feed on corn leaves and in developing tassels, stalks, and ear tips. European corn borer damage reduces grain quality, increases grain loss, and leads to problems at harvest.

What do European corn borers look like?

Egg: European corn borer eggs are laid in overlapping masses that resemble fish scales (Figure 1). The eggs change from glossy or creamy white when freshly laid to a darker color as hatch approaches. When close to hatching, the black head capsules of the larvae become visible through the eggshell. The “blackhead stage” of corn borer development indicates that the larvae are likely to hatch within 24 to 36 hours.

Larva: European corn borer larvae are creamy-white to light gray in color with rows of small brown spots along the body (Figure 2). The head capsule is dark or reddish-brown. The larvae mature through five instars and grow to ¾ to 1 inch long.

Pupa: European corn borer pupae are smooth reddish-brown and about ½ inch long, with a rounded head and pointed tip (Figure 3).

Adult: The adult moths are small with a wingspan of about 1 inch. At rest, the wings form a triangular shape (Figure 4). Female moths are light tan while males are slightly smaller and darker with more distinct markings. The moths are identifiable by the irregular wavy lines across the forewings.

Life cycle and biology of European corn borer

European corn borer has two generations per year in most of Wisconsin, but only one generation in the northern counties. The overwintering stage in Wisconsin is the fifth instar larva. Winter is spent in tunnels in corn stalks and large-stemmed weeds surrounding fields. As temperatures reach 50°F in the spring, the larvae pupate and moths emerge and fly to aggregation sites to mate. The moths seek out areas of dense grass that provide necessary moisture and habitat for mating. Mated females fly to corn fields at night and lay masses of 15 to 30 eggs on the undersides of corn leaves near the midrib. Female moths lay an average of 400 eggs each.

In southern Wisconsin, egg laying by first-generation moths occurs from late May to mid-June. Early-planted corn in the 10-leaf stage is most attractive for egg laying by the spring flight of moths. Eggs hatch in six days at 70°F and first-instar European corn borer larvae crawl into the whorl of corn plants (Figure 5).

The first and second-instar larvae initially feed on leaf tissue in the whorl for several days, and then some begin boring into the midrib. At about the third instar, larvae begin boring into forming tassels and stalks. The larval period includes five instars and requires approximately 24 days to complete. Pupation takes about 12 days before adult moths emerge. The second generation of moths lay eggs over a longer period. Moths of the second, or summer flight, begin emerging in late July or early August. During warm years, a third generation may start, but rarely matures before winter. Only larvae that reach the fifth instar before winter are able to survive until the following spring.

Early-planted corn in the mid-whorl or 10-leaf stage is most attractive for egg laying by spring moths. Late-planted corn or late maturing varieties are preferred egg laying sites for the summer moths, with sweet corn being the favored host.

What are the symptoms of European corn borer damage?

Early European corn borer larval feeding results in irregular “pinholes” in the whorl leaves (Figure 6). As the leaves unfurl from the whorl, the pinholes expand and become more uniform, giving the leaves a “shothole” appearance (Figure 7). Pinholes and shotholes inside the whorl indicate recent feeding and the potential to find live larvae.

Sawdust-like frass may be visible where larvae bore into the midribs and stalks (Figures 8-9). First-generation damage weakens the stalk and can lead to breakage or infection by pathogens such as stalk rot later in the season.

Second-generation European corn borer larvae bore into the stalk, tassel, and ear shanks, often causing damage to the ear zone (Figure 10). Stalks and tassels may break and ears may drop to the ground. Larvae may also directly damage kernels and cobs, allowing fungal pathogens to enter the ear (Figure 11).

How do you scout for European corn borer?

The Wisconsin Department of Agriculture, Trade and Consumer Protection (DATCP) tracks European corn borer moth flights in Wisconsin through its Pest Monitoring Network. A network of black light traps across the state provides information about emergence, abundance and seasonal occurrence of nocturnal pests.

Blacklight traps provide useful information about European corn borer but should not be a replacement for field scouting.

Scout for both the first and second generations of European corn borer larvae in susceptible fields.

Start first generation scouting when corn reaches 18 inches tall. Check 20 consecutive plants in five areas of the field (100 plants total). Look for leaf feeding and the characteristic “pinholes”. Pull the whorl leaves from two infested plants, unroll the leaves, and check for live European corn borer larvae. Calculate the percentage of plants with recent feeding and the average number of live European corn borer larvae per plant.

Scout for the second generation of European corn borers by concentrating on the latest planted corn and looking for the white egg masses. Carefully examine the undersides of leaves (near the midrib) on the leaves above and below the ear. Check at least ten plants in five areas of the field (50 plants total).

If infestations are heavy and go unnoticed, ears may drop and stalks may break in the fall (Figure 12).

What is the threshold for European corn borer treatment?

In fresh market sweet corn, treatment may be warranted through the early silk stage if 5% of plants have egg masses, larvae, or leaf damage. Treatment should be repeated every three to five days if at least one unhatched egg mass remains per 20 plants.

For processing sweet corn, treatment is justified during the whorl stage if 25% of the plants are infested with egg masses or live larvae or show signs of feeding. Treatment during the late-tassel to silk stage may be considered if eggs or live larvae are found on 4-5% of plants. Repeat treatments every three to five days as needed.

In late-planted processing sweet corn, treatment is warranted when second generation eggs or larvae are found on 4-5% of plants with emerging tassels.

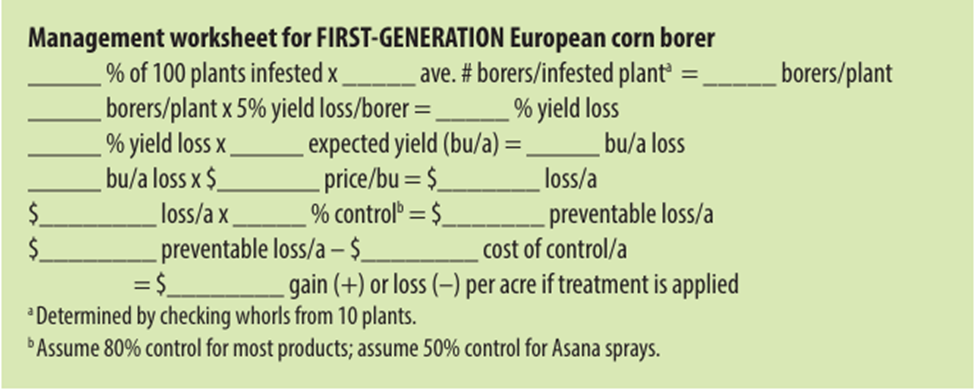

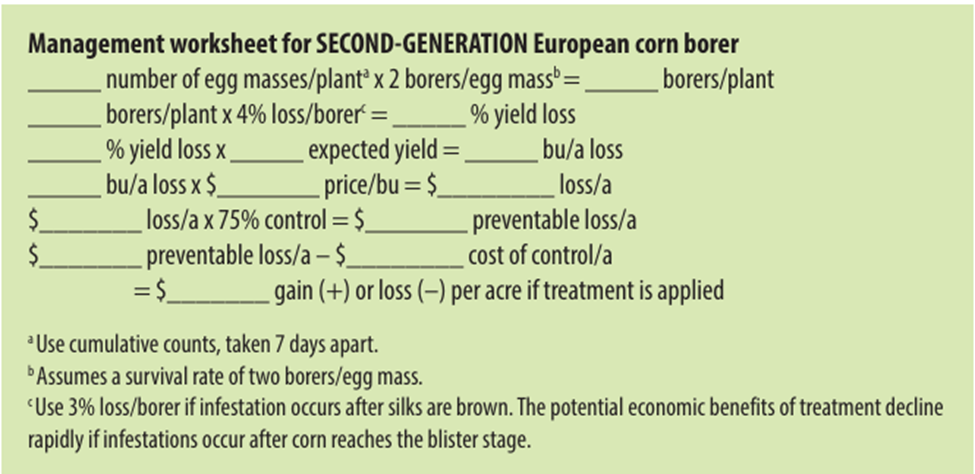

Insecticide treatments for European corn borers are not always needed. Management worksheets have been developed to help growers assess the economic benefit of treating first- and/or second-generation European corn borers. To utilize these worksheets, it is essential to scout fields at appropriate times. The first-generation management worksheet (Figure 13) requires the number of plants infested and the number of larvae per plant. The second-generation worksheet (Figure 14) requires the number of egg masses found per plant.

Integrated pest management (IPM) strategies for European corn borer

Cultural Control

Cutting corn for silage or shredding it for fodder can kill overwintering European corn borer larvae if the remaining stubble is two inches or less. Dry-stalk shredding may kill 80% of European corn borer larvae. Larval populations can be reduced by plowing under crop stubble; however, certain plowing practices increase potential soil erosion and may be unacceptable.

Biological Control

Natural enemies, such as Trichogramma wasps, parasitize European corn borer eggs and larvae. Purchasing and releasing natural enemies may not be economically feasible, so it is important to preserve the natural enemies already present in the field.

Chemical Control

Insecticides may be warranted to control European corn borer. Refer to Pest Management in Wisconsin Field Crops (A3646) for European corn borer insecticide recommendations (p. 68-69).

Application timing is critical. The control window for first-generation European corn borers is between 800 and 1,000 growing degree-days (modified base 50°F). This often occurs between mid-June and early July in southern Wisconsin. For the second generation, the treatment window is right before egg hatch, between 1,500 and 2,100 growing degree-days. If possible, target treatments when the black heads of the larvae are visible in the egg masses.

Planting transgenic Bt corn is another control method for European corn borer and the primary method used in Wisconsin to manage this pest in grain corn. Bt corn expresses the soil bacterium Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) toxin that is lethal when ingested by corn borer larvae.

Review “The Handy Bt Trait Table” in Pest Management in Wisconsin Field Crops (A3646) (p. 57-58) for a list of trait packages that are marketed to control European corn borer. If you plant transgenic Bt corn, be sure to plant the required refuge and follow recommendations to delay resistance.

European corn borer response and management options

Monitor weather conditions and crop growth stage to determine optimal timing for insecticide applications, as needed.

Always apply insecticides according to label instructions and consider factors such as application method, rate, and pre-harvest intervals.

Environmental and ecological considerations for European corn borer treatment

Minimize pesticide use whenever possible to reduce potential impacts on non-target organisms, biological controls, and environmental health.

Implement IPM practices that promote biological diversity and ecosystem resilience.

References

Additional resources

Use information from DATCP’s Pest Monitoring Network of black light traps to track European corn borer moth flights in Wisconsin to optimally time field scouting.

Sign up for Insect Pest Text Alerts from the Bick Lab at UW-Madison to be alerted about European corn borer in your area.

For assistance with European corn borer management and other agricultural pest issues, contact your local agricultural extension office.

Last Updated: June 23, 2025

Reviewed by: Krista Hamilton (DATCP)

Featured cover photo by Krista Hamilton.

Managing Black Cutworm in Wisconsin Corn Fields

Managing Black Cutworm in Wisconsin Corn Fields Managing Soybean Aphids in Wisconsin Soybean Fields

Managing Soybean Aphids in Wisconsin Soybean Fields Managing Corn Earworm in Wisconsin Corn Fields

Managing Corn Earworm in Wisconsin Corn Fields Managing Western Bean Cutworms in Wisconsin Corn Fields

Managing Western Bean Cutworms in Wisconsin Corn Fields