Currants

CURRANTS

Crop Profile

Get Involved!

Red, white, pink and black currants all belong to the Ribes genus within the Gooseberry family. Black currants belong to Ribes nigrum, while red, white and pink currants are Ribes rubrum.

Currants are an extremely cold hardy crop native to northern latitudes of Europe, Asia and North America. Currants are commonly grown in Scandinavia and northern Europe with Russia and Poland producing the vast majority of the world’s crop. Currants were brought over from Europe to the United States in the early 1800s and were widely grown in New England, especially New York, in the late 1800s.

The fate of currants in the United States began to change in the early 1900s with the introduction of white pine blister rust. Plants in the Ribes genus, especially black currants, served as a host for the fungus and threatened the white pine timber industry. A federal ban on the cultivation of currants was implemented in the 1920s and remained in place until 1966. Throughout the 1930s and into the 1940s, thousands of Civilian Conservation Corps members participated in a campaign to eradicate plants in the Ribes genus. Today, the laws regarding the cultivation of currants today vary state to state. In the Midwest, Michigan and Ohio still have restrictions on the varieties of black currants that can be grown.

Currants are rising in popularity but remain a niche crop in the United States. In 2017, the latest year for which there is data, there were over 500 acres of currants being grown with Connecticut, New York and Washington leading the way. Black currants are most widely grown because of their ease of production, processing capabilities, and nutritional qualities.

Black currants are considered a processing berry with most going to juice production and others for jam, wine and liqueur. They are considered a superfood with three times more Vitamin C than oranges and high levels of antioxidants. Red and white currants are less nutritious but more palatable for fresh eating, even though they are a tart berry. Red and white currants are excellent for baking and make good jams and jellies but do not juice well. All currants freeze well, especially black currants, and store well in the fridge.

Production

From an agronomic standpoint, currants are an attractive crop for Upper Midwest producers. They are very cold hardy, grow on a wide range of soil types and pH levels, yield 6000 pounds per acre or more, can be machine harvested, and hold on the bush to allow for a long harvest window. Additionally, currants grow well in partial shade, making them suitable for use in agroforestry systems.

Currants grow as a multi-stemmed bush reaching about five feet tall and three to four feet wide. They flower in early spring and are usually harvested in July. Most cultivars are hardy down to Zone 3 but don’t tolerate high summer temperatures very well. Currants do not compete well for moisture or nutrients because of their shallow roots, so weed barriers such as landscape fabric or mulch and drip irrigation are recommended. Currants tolerate a wide range of soil pH but do best in slightly acidic soil between 6.0-7.0. They are heavy feeders and require annual fertilizer applications in the spring or early summer. Most currants are self-fruitful and do not need a pollinizer.

Currants are usually propagated by cuttings but can also be planted from dormant bare root plants. Plants are traditionally grown as freestanding bushes and spaced according to harvest method. Plants that will be hand harvested are spaced 4-6 feet apart within the row and grown as individual plants for better maneuverability when picking. For mechanical harvesting, plants are spaced about two feet apart within the row and allowed to grow into a dense hedgerow. Rows are spaced 10-12 feet apart to leave enough space for the harvester.

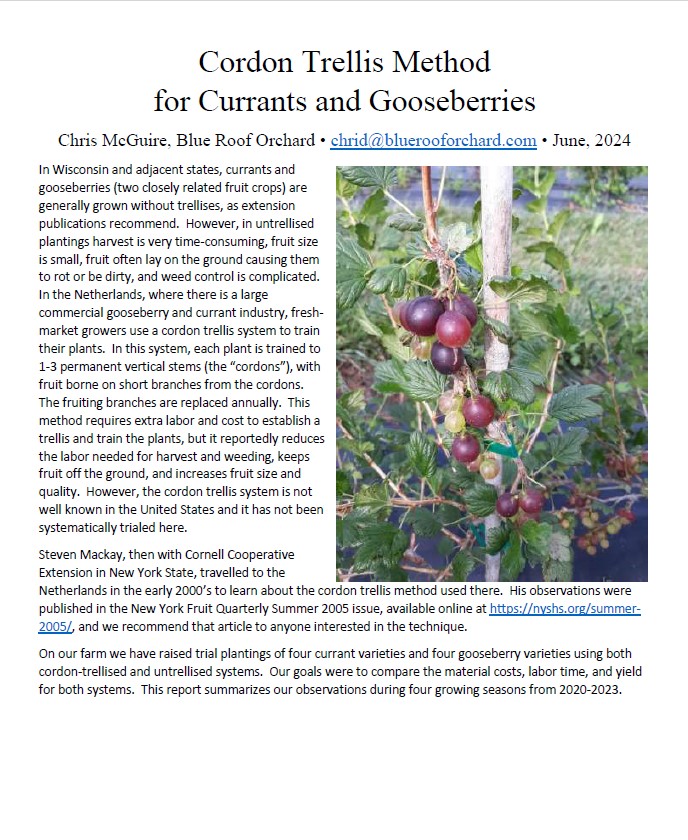

Hand harvesting is the most practical option for small scale growers in the Midwest. However, it is extremely labor intensive, accounting for about 60-70% of total labor costs. To improve the efficiency of hand harvesting, currants can be grown on a trellis system. In a trellis system, plants are pruned to 1-3 permanent vertical stems, or cordons, and trained to vertical stakes on a wire trellis system. Fruit is produced from horizontal branches off the cordons. Shoots emerging from the crown are continuously removed. In addition to reducing labor when hand harvesting, trellising improves fruit size and quality and reduces the risk of disease. Red and white currants are often grown as a trellised fruit in the Midwest for fresh markets while black currants are grown in hedgerows and mechanically harvested for use as a processing berry.

Mechanical harvesters, such as blueberry harvesters, save a lot of labor but can only be justified in larger scale plantings. Other berry crops, such as aronia and honeyberries, can also be machine harvested with the same equipment when grown in hedgerows. Many factors determine the effectiveness of machine harvest, including the timing and varieties grown. Disadvantages of mechanical harvesters are their expense, lack of control, and incompatibility with intercropped plants in agroforestry systems.

Harvest usually begins in the second growing season with peak production in about year five. Yields will vary from variety to variety and can range from 2000-8000lbs per acre and 5-10lbs per bush. Ripe berries will hold on the plants for a couple weeks but will gradually start to soften thereafter. Berries do not ripen uniformly so plants are sometimes harvested two or three times throughout the season.

Currants continuously send up new shoots from the crown and require annual pruning. Pruning is very similar to blueberries where wood more than four years old is removed. Black currants are more vigorous than red and white currants and send out many shoots from the crown, which need to be pruned out more often. Some growers mechanically prune, or coppice, their black currants every three to four years with a mower. This takes one third to one quarter of the field out of production every year but dramatically reduces hand labor for pruning.

Currants suffer from few disease and pest problems. White pine blister rust, the disease responsible for their 20th century ban, does not affect currants in a serious way and newer varieties have good resistance. Powdery mildew can be an issue in the southern part of their range and in high tunnel production. Resistance varies from variety to variety. Spotted wing drosophila (SWD) has not been a major issue thus far. Currant cane dieback is perhaps the most concerning. This fungal disease caused widespread damage a century ago before the ban and is reemerging in the Northeast and Midwest. Red and white currants seem to be more susceptible.

For more information on currant production, visit the University of Minnesota Extension or Cornell University websites.

Research Status and Priorities

Currants have not received the same amount of attention in the United States as they have in Europe and Russia. Since the federal ban in the United States was lifted in 1966, research on currants has expanded, with many Extension services at public universities across the northern tier of states evaluating their agronomic potential in the last two decades. New York has taken the lead in terms of Extension support and building markets under the guidance of Cornell University researchers.

McGinnis Berry Crops in British Columbia, Canada operates the only currant breeding program in North America. Their stated goal is to breed varieties of black currants suited for North American growing conditions. Their objectives include resistance to white pine blister rust and powdery mildew, high yields, tolerance to late spring frost, and outstanding fruit qualities. In addition, cultivars are being bred for North American palates, with high sugar and low acidity.

In the Midwest, the University of Wisconsin-Madison, University of Illinois, Savanna Institute, and partner farms are collaborating to support currant production and help develop markets with an emphasis on black currants. Research has focused on variety performance, biochemical analyses of fruit, the economics of different production systems, and consumer preferences. The University of Illinois has investigated the shade tolerance of black currants for use in agroforestry systems. Research bulletins from these studies can be found in the “Resources and Information” section of this webpage.

Markets

Marketing is the biggest challenge for growers. American consumers are accustomed to eating sweet fruit (blueberries, strawberries, raspberries) and currants are tart. Currants are also unfamiliar to most Americans. Nevertheless, currants have many qualities that make them attractive to consumers.

Black currants are one of the most nutritious fruits in the world, making them appealing to health-conscious consumers in value-added products. Black currants are typically sold as a processing berry, and most are turned into juice. There may be opportunities to sell to jam makers or breweries, cideries, and wineries, as they make a valuable addition to beverages for their flavor and color.

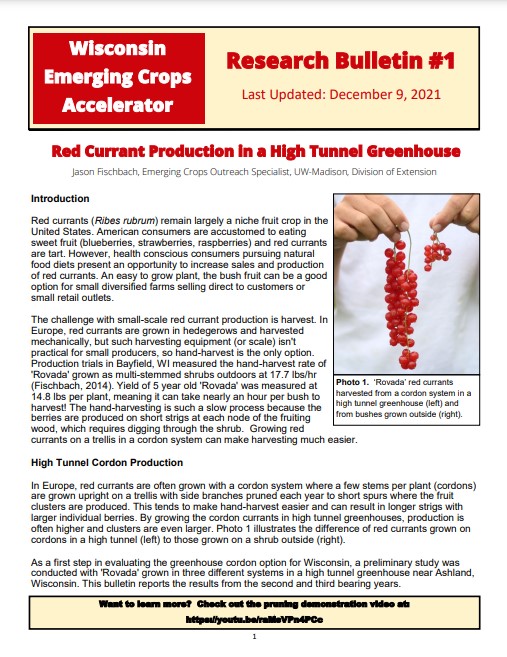

Red and white currants are slightly easier to market. They have the potential for fresh eating, are excellent in baked goods, and make good jams and jellies. When selling direct to consumers, providing recipes and suggestions for eating are key. Seeking out ethnic groups who are more familiar with the fruit, such as Europeans, can be a good marketing strategy. Currants tend to sell poorly in grocery stores, but small retail outlets such as co-ops may be an option.

Direct to consumer prices for fresh berries can vary widely but average $4/pint for conventional and $5-$7/pint for organic. A few wholesale markets may be available, particularly for jam and juice makers, breweries, and winemakers. These markets normally prefer a pureed product with prices ranging from $2.50-5/lb. Growers are advised to start small and seek out markets before planting.

Plant Material

Plants are usually sold as dormant bare root plants or plugs. Choose varieties that are best suited for your production system, climate, and markets. Varieties differ in their resistance to diseases, flowering and ripening time, productivity, and fruit quality. Additionally, a few varieties are not self-fruitful and require a pollinizer.

The University of Minnesota Extension has variety descriptions and recommendations for growers in the Upper Midwest. Cornell University maintains a list of nurseries selling currant plants. Commercial availability of planting stock is limited, so growers are advised to order early (November, December).

Resources and information

Read

Watch

(Chris McGuire, Blue Roof Orchard)

(Jason Fischbach, UW-Madison)

(Eric Wolske, University of Illinois, and Chris McGuire, Two Onion Farm)

(Eric Wolske, University of Illinois)

Listen

More Resources

Cornell University – Gooseberries and Currants

North Dakota State University

University of Minnesota Extension

University of Wisconsin-Madison Fruit and Nut Compass (financial planning tool)

Wisconsin Berry and Vegetable Growers Associations

Wisconsin Fruit (UW Fruit Program)