Honeyberries

HONEYBERRIES

Crop Profile

Get Involved!

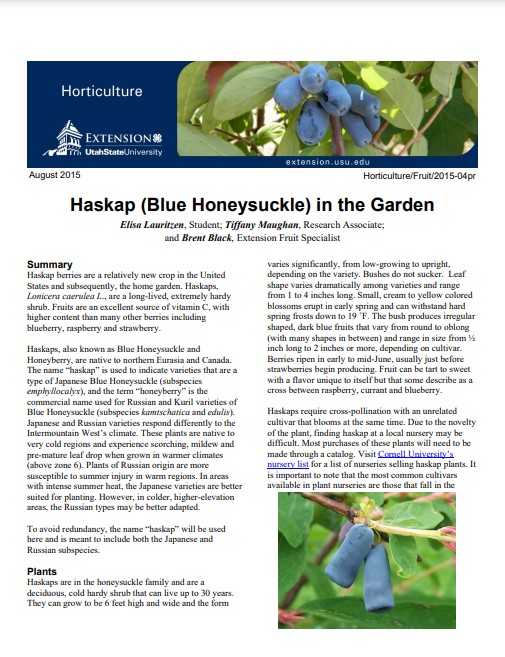

Honeyberries, Lonicera caerulea, are a relatively new crop to North America that go by many different names, including haskaps, blue honeysuckle, and sweet berry honeysuckles. The people of the island of Hokkaido in Japan have a history of eating honeyberries going back hundreds of years. They are a member of the honeysuckle family native to the boreal forests of Russia, Japan, North America, and the Kuril Islands. Honeyberries from each of these regions have been classified as separate subspecies with distinct differences in traits such as productivity, time to maturity, uniformity of ripening, and tendency to drop their berries when ripe.

Honeyberries are an irregular-shaped, elongated, blue berry that grow on bushes. Plants are extremely cold hardy and can be grown in USDA zones 1-8. They are easy to manage, growing 3-6′ tall with no suckering or thorns. Minimal pruning is needed. Unlike blueberries, plants tolerate of a wide range of soil pH, from 5.5-8. The earliest maturing varieties ripen in June, two weeks before strawberries. Flowers appear six weeks before the last frost and are hardy down to at least 20F. Varieties require a compatible pollinizer with an overlapping bloom time in close proximity. Plants will begin bearing a few fruit in years one and two, but three to four years are required for large quantities. Plant and fruit characteristics will vary depending on the variety.

Honeyberries have a flavor described as a cross between a blueberry and a raspberry with an added zing. They can be eaten fresh or used in processed products such as pastries, jams, juice, wine, ice cream, yogurt, sauces, syrup and candies. The skin is thin and dissolves quickly. Seeds are tiny, much like a kiwi. Honeyberries make a high quality wine with a deep burgundy color. The nutritional profile of honeyberries are outstanding. The berries are higher in antioxidants and Vitamin C than blueberries.

Honeyberries are remarkably free of pests and diseases. Because they set fruit so early, insect pests rarely affect production. Deer may browse younger plants but leave older wood alone. Birds, especially cedar waxwings, pose the greatest threat and bird netting is recommended. Powdery mildew can affect leaves in mid-summer, after harvest, but does not seem to affect long term plant health. Susceptibility varies significantly between varieties.

Research Status and Priorities

Because honeyberries are a relatively new crop, there are few breeding programs in North America. The two main programs are at Oregon State University, which was led by Dr. Maxine Thompson, now deceased, and the University of Saskatchewan, led by Dr. Bob Bors. The breeding program at Oregon State University has focused on using Japanese plant material to breed varieties adapted to the Pacific Northwest. The University of Saskatchewan has been breeding primarily with Japanese, Russian and Kuril genetics. Varieties from this program are likely better adapted to Wisconsin’s climate.

Since breeding began in 2002, the University of Saskatchewan has released nine varieties. The early varieties, including Tundra, Borealis and the Indigo series (Indigo Gem, Indigo Treat, Indigo Yum), were a significant improvement over varieties available on the market at the time but have since been replaced by better varieties. Aurora was the next release, with Honey Bee as its pollinizer. These are the most productive of the early ripening varieties and should be planted together for cross-pollination. Today, Aurora is the most popular variety in the world. The Boreal series (Boreal Beauty, Boreal Beast, and Boreal Blizzard) were the next releases. These extended the harvest season by being late ripening and also possessed superior qualities such as flavor and large berry size. When asked to pick top performing varieties for Wisconsin, Dr. Bob Bors from the University of Saskatchewan suggested Aurora and and Boreal Beast. Both have high flavor ratings and will cross pollinate.

As breeding efforts have dramatically improved the flavor, yield, and mechanical harvestability over the last 20 years, this crop has tremendous potential in Wisconsin. With more research on variety performance and marketing campaigns to raise awareness, this berry will no doubt become the “broadly feted darling of farmer markets, CSA’s, grocery stores, and nurseries in the coming decades,” as Erin Schneider of Hilltop Community Farm put it.

Markets

Honeyberries are often grown as part of a diversified fruit operation with other alternative berries. They are usually marketed direct to consumers through U-pick, pre-picked on-farm sales, and farmers markets. Other marketing opportunities will be highly dependent upon local markets and may include cottage industries utilizing the fruit for jam, jelly, juice, or dried fruit. Others may include wineries, breweries, bakeries, restaurants, and local food coops.

Plant Material

Cornell University maintains a list of nurseries selling honeyberry planting stock. Given the limited availability of honeyberries in the United States, finding good rootstock and preferred varieties can be a challenge. It is advised to order early.

Resources and information

Read

The University of Saskatchewan Fruit Program webpage has many more resources on research and breeding efforts in Canada.

Watch

Jim Riddle (Blue Fruit Farm, Winona, MN)

Dr. Brian Smith (University of Wisconsin-River Falls)

Listen

More Resources

Montana State University

North Dakota State University

University of Saskatchewan Fruit Program

Utah State University Extension

University of Wisconsin-Madison Fruit and Nut Compass (financial planning tool)

Wisconsin Berry and Vegetable Growers Associations

Wisconsin Fruit (UW Fruit Program)