Soil health describes the ability of soil to perform essential functions, which are influenced by management practices in agricultural systems. The most common definition is from the USDA-Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS), which defines soil health as “the continued capacity of soil to function as a vital living ecosystem that sustains plants, animals, and humans.”

Soil health is a comprehensive concept that unites the chemical, physical, and biological properties of soil. These properties can be managed and measured separately, but it is important to realize that it is the interaction of these properties that creates and sustains soil function and ultimately, our production systems. This comprehensive thinking about soil properties is why the soil health concept is valuable for agriculture in Wisconsin.

This article highlights the characteristics of healthy soil and describes how these characteristics, and soil health generally, can contribute to sustainable crop production and indirectly impact society beyond the farm field.

Characteristics of Soils

Healthy soils are crucial for sustainable agriculture1. Productivity, environmental quality, and farmer income can suffer over the short and long term when soil does not function to its full potential. Here we review the physical, biological, and chemical properties of soil, as well as how soil organic matter (SOM) is connected to all these properties.

Physical Properties of Soil

Soil Texture

Soil texture refers to the proportion and distribution of differently sized particles in the soil. Clay particles are the smallest in size (<0.002 mm in diameter), followed by silt (0.002 – 0.05 mm in diameter), and then sand particles (0.05 – 2.0 mm in diameter).

Soil texture is an inherent property of soil, meaning it is not greatly influenced by different management practices. It influences several other soil properties and functions including but not limited to:

- Internal drainage

- Surface water infiltration rate

- Water holding capacity

- Organic matter and nutrient holding capacity

- Soil structure formation

Soil Structure

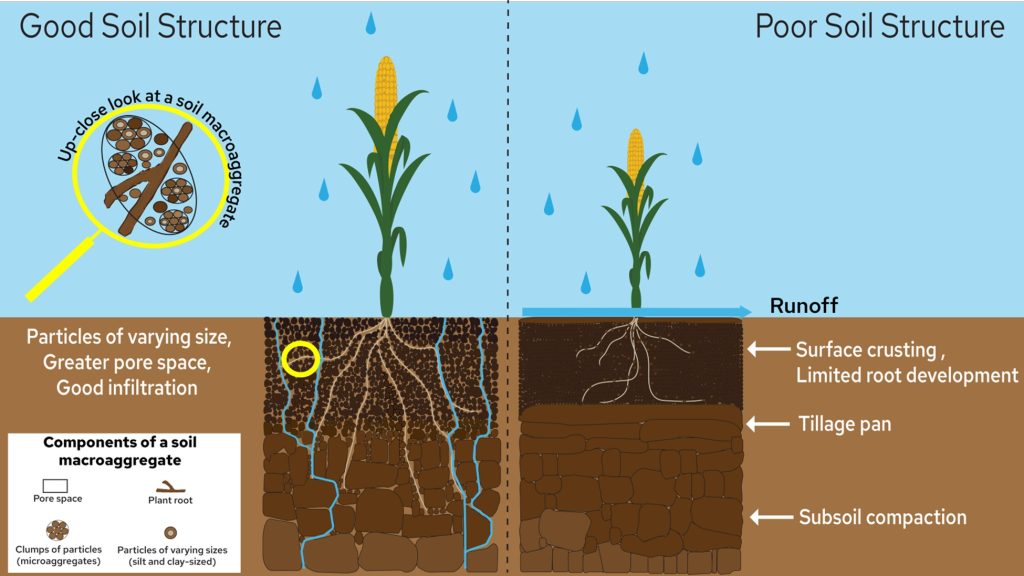

Soil structure refers to the grouping and arrangement of individual soil particles (sand, silt, clay) along with organic matter into larger pieces called aggregates.2

Healthy soils have high aggregate stability, meaning they can maintain their structure and resist the impact of external pressures such as rainfall or compaction from equipment traffic. Powdery soil or soil with large clods are indicators of poor soil structure and health.2

Good soil structure allows for air and water movement within the soil via greater pore space. Poor soil structure decreases this movement and can lead to surface crusting and compaction.2

Good soil structure allows for extensive root development, whereas poor structure can limit root development.2

Water Holding Capacity and Infiltration Rate in Soils

Water holding capacity describes the amount of water a soil can hold, but not all the soil water in a soil is available to crops. Available water capacity is the amount of water that a soil can store for crops to use.2 For example, clayey soils have greater water holding capacity than loams, yet loams generally have greater plant available water capacity.2

Too little water holding capacity causes plants to wilt, while too much water (e.g., too much rain/irrigation and/or poor drainage capacity) can reduce plant vigor.2

Healthy soils have a wide range of pore sizes. Large pores take in water during rainfall events and connect to medium and small pores that store it for later use. A range of pore sizes enables increased water storage, improving drought resiliency.2

The infiltration rate is the amount of water that moves into the soil profile, as opposed to running off the soil surface. Increasing a soil’s capacity for infiltration is especially important during intense rainfall events, which are increasingly frequent in Wisconsin.2

Adequate infiltration is crucial for water availability to crops, groundwater recharge, resiliency to flood events, decreasing erosion, and timely field access.2

Visit the Soil Health Nexus for more resources and references on soil physical properties.

Biological Properties of Soil

Soil Nutrient Cycling

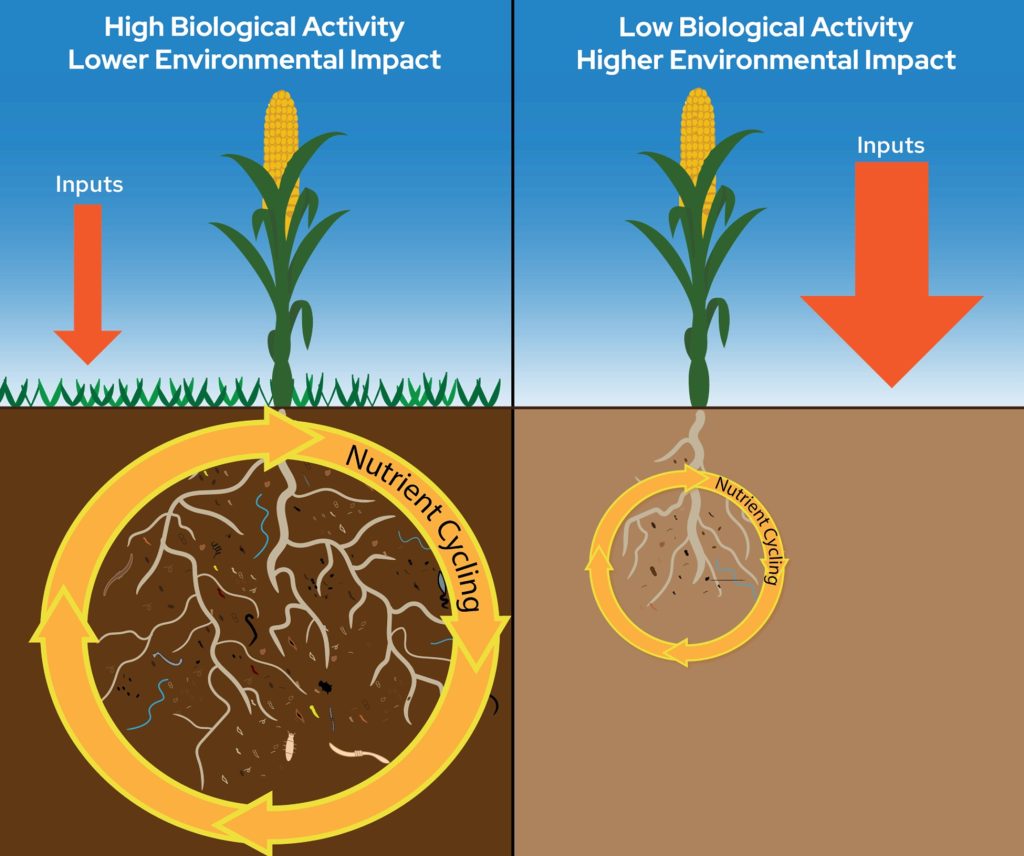

Soil microorganisms are the key engineers of nutrient cycling and transformations, but larger soil organisms such as nematodes, arthropods, and earthworms also play key roles.2,4

One of the most essential services that larger soil organisms provide is breaking down organic matter such as plant litter, into smaller pieces that are more accessible to microbes. Microorganisms then further decompose and transform the organic matter into nutrients available for plants. This combined process is known as nutrient cycling and is a critical factor in soil fertility.2,4

Soil often contains important nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorus, but they are not necessarily in a plant-available form. Soil biology can help release nutrients by breaking down the larger compounds they are a part of. Effective nutrient cycling can also reduce the need for synthetic nitrogen fertilizer inputs.2,4

Soil Organisms

Soil Bacteria

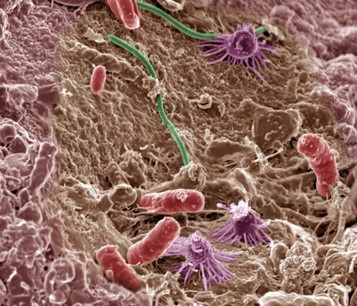

Bacteria are single-celled microorganisms found in large numbers almost everywhere on earth. They decompose organic matter, break down pesticides and pollutants, and play a key role in storing and cycling nutrients. Nearly all soil bacteria help decompose organic material, while specific types fix nitrogen and cycle it. Additionally, some bacteria are pathogens and can harm plants. Bacteria can live throughout the soil, but they are especially concentrated around roots (the rhizosphere).2,4

Soil Fungi

Fungi are microorganisms with various shapes, sizes, and functions. They typically grow as long, thin strands called hyphae. Many fungi break down hard-to-digest organic matter (like lignin, which gives plants their rigid structure) and release nutrients for plants. Some fungi are harmful pathogens that can colonize plant parts or even other organisms, while others are predators that trap nematodes or parasitize insects.2,4 On the other hand, some fungi are beneficial, such as arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF). AMF form partnerships with plant roots, improving the plant’s nutrient and water uptake in exchange for carbon.

Soil Protists

Protists are mobile microorganisms that mainly consume bacteria in the soil. When protists eat bacteria, they release nitrogen into the soil in a form that plants can use. They release nitrogen into the soil because the bacteria contain more nitrogen than the protists need. Protists live in water films on and in the soil and are most abundant near plant roots in the upper few inches of soil.3,4

Soil Nematodes

Nematodes are tiny, non-segmented roundworms. Nematodes can be predators, bacterial-feeders, fungal-feeders, or plant parasites. Like protists, they can enhance nutrient cycling in soil by feeding on bacteria and other microorganisms. Nematodes move through the soil by navigating water films in large pore spaces.4,5

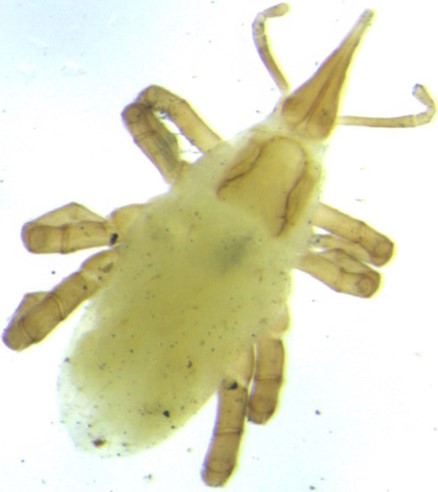

Soil Arthropods

Photo by Dane Elmquist

Arthropods are invertebrates with jointed legs and hard exoskeletons. Based on their soil functions, they can be grouped as decomposers, predators, herbivores, and microbe-feeders. While herbivores can sometimes be pests, most soil arthropods are beneficial. For example, decomposers shred organic materials, increasing surface area for microbial colonization and speeding up decomposition. Predators kill and eat other organisms, helping control pests as biological control agents. Arthropods are most abundant in the top five inches of soil and on the soil surface. Common soil arthropods include springtails, mites, beetles, ants, spiders, centipedes, and sowbugs. 4,5

Earthworms

Earthworms have long, segmented bodies. Their activity affects soil structure, water movement, nutrient cycling, and plant growth. Earthworms are usually grouped into three categories based on their feeding and burrowing habits. Epigeic species stay close to the surface and feed on plant litter. They do not create permanent burrows. Endogeic species feed on soil and organic matter, burrowing through the soil for food. They live in horizontal, non-permanent burrows primarily in the top few feet of soil. Anecic species live in permanent vertical burrows that can extend several feet deep. They pull litter from the soil surface into their burrows and deposit nutrient-rich casts (earthworm poop) on the soil surface.4,5

Visit the Soil Health Nexus for more resources and references on soil biological properties.

Chemical Properties of Soils

In general, soil chemical properties are related to nutrient availability, cation exchange capacity (CEC), and pH. These properties are well-studied and soil tests have been developed to guide management.

Nutrients and Cation Exchange Capacity

There are 17 essential plant nutrients. They are divided into four categories based on the quantity used by the crops: structural nutrients which account for most of the total dry plant biomass (carbon, oxygen, and hydrogen, obtained from atmosphere and environment), macronutrients (i.e. the nutrients needed in the largest quantities: nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium), secondary nutrients (nutrients needed in large quantities, but generally provided by the soil: sulfur, calcium, and magnesium), and micronutrients (nutrients needed in low quantities: zinc, manganese, copper, iron, molybdenum, boron, chloride, and nickel). Find more information about essential plant nutrients and the ways they interact with one another in Crop Nutrients 101.

In general, nutrients exist in the mineral fraction of soils bound within soil organic matter or crop residue (e.g. nitrogen and phosphorous, which need soil biology to release them), or in an ionic form (e.g. potassium (K+) and zinc (Zn2+)) which are then bound to cation exchange sites in soil. Cation exchange capacity (CEC) is a soil’s ability to hold onto and exchange positively charged ions (e.g. K+, Zn2+, etc.,) and greater CEC is generally advantageous from a soil fertility and crop nutrition standpoint. CEC is strongly affected by clay minerology (an inherent, unchanging soil property) and also by organic matter. Soil pH (level of acidity) and soil moisture dictate the balance between available nutrients in soil solution and unavailable nutrients bound to the soil.

There are several nutrients where soil tests (or extractions) have been calibrated to indicate plant-available nutrient levels by relating their soil concentrations to crop yield (e.g. Bray-1 P & K, ammonium acetate Ca & Mg, and 0.1N hydrochloric acid Zn). These soil tests can help when deciding if these nutrients should be applied to crops, and whether nutrient applications will result in economic responses).2

pH

Soil pH, the measure of soil acidity/alkalinity, affects the availability of nutrients to plants. Optimal soil nutrient availability for most plants happens at a pH of 6.0-7.0, but exceptions exist. This pH range is best for plant roots to take up most nutrients from the soil.2 Soil test laboratories offer pH analysis which can then be used to guide lime application rates to manage soil acidity.

Soil CEC inherently affects the ability of soil pH to change (e.g., soil pH buffering capacity). Greater CEC soils (clayey soils) will require more lime to achieve a change in pH compared to soils with lower CEC (e.g., sandy soils). Similarly, the effect of a liming application to a soil with greater CEC will be longer lasting than that to a soil with low CEC.

Visit the Soil Health Nexus for more resources and references on soil chemical properties.

How does soil organic matter influence all three components of soil health?

Soil organic matter (SOM) is a central component of soil health that influences chemical, physical, and biological properties. SOM consists of plant and animal residues, living and dead microbes, and substances produced through decomposition, and is approximately 50% organic carbon in composition.6

The amount of SOM that exists in any agricultural field is a combination of all the soil forming factors (climate, organisms, topography, parent material, and time) as well as management history. Recent studies have demonstrated there is a relationship between SOM and corn yields, showing corn yields generally increasing with increased SOM up to 4% in Wisconsin7. Given that SOM is a common measurement that has documented connections with productivity and many other soil properties, focusing on SOM is a great place to start when thinking about soil health.

Chemical Properties

Greater amounts of soil organic matter are associated with greater cation exchange capacity, as soil organic matter also provides exchange (binding) sites for plant nutrients.

Physical Properties

Greater amounts of soil organic matter are associated with greater aggregate formation and stability. The amount of aggregation can be management-related as well, but having more organic matter will lead to increasing the soil’s ability to form aggregates, which in turn can lead to greater water-holding capacity and infiltration.

Biological Properties

Greater amounts of soil organic matter are associated with greater biological activity. While there can still be a range in biological activity across soils with similar SOM contents, SOM functions as the primary food source for microorganisms.

It’s also important to note that SOM is influenced by soil properties. SOM generally increases with silt and clay content, because binding with these particles can protect SOM from decomposition. Conversely, SOM generally decreases with increasing sand content.

Conclusion

As farmers, industry, and policymakers work to improve soil health, it is essential to know what goals and soil characteristics they are targeting. Understanding how to improve soil health through practices and measuring soil health accurately is complex and is still being untangled by researchers. However, the basics of healthy soil, such as good structure, water holding capacity, infiltration, nutrient cycling, and high levels of soil organic matter and biodiversity, can often be seen and felt in the field and are worthy guideposts for farmers as they manage for a sustainable future.

For more in-depth reading, check out the resources cited throughout the article.

Resources and Citations

- Kibblewhite, M.G., Ritz, K., Swift, M.J. (2008). Soil health in agricultural systems. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 363, 685-701.

- Magdoff, F., Van Es, H. (2021). Building Soils for Better Crops. Sustainable Soil Management, IV Ed. 401pp. Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education (SARE) Program, National Institute of Food and Agriculture, USDA.

- Jastrow, J.D., Miller, R.M. (1998). Soil aggregate stabilization and carbon sequestration: Feedbacks through organomineral associations. pp 207-223 in Soil Processes and the Carbon Cycle, CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL.

- Orgiazzi, A., Bardgett, R.D. , Barrios, E., Behan-Pelletier, V., Briones, M. J. I., Chotte, J. L., De Deyn, G. B. , Eggleton, P., Fierer, N., Fraser, T., Hedlund, K., Jeffrey, S., Johnson, N. C., Jones, A., Kandeler, E., Kaneko, N., Lavelle, P., Lemanceau, P., Miko, L., Montanarella, L., de Souza Moreira, F. M., Ramirez, K. S., Scheu, S., Singh, B. K., Six, J., van der Putten, W. H., Wall, D.H. (2016). Global Soil Biodiversity Atlas. European Commission, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg.

- Hopwood, J., Frischie, S., May, E., Lee-Mader, E. (2021). Farming with Soil Life: A Handbook for Supporting Soil Invertebrates and Soil Health on Farms. 128pp.Portland, OR, The Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation.

- Pribyl, D.W. (2010). A critical review of the conventional SOC to SOM conversion factor. Geoderma. 156(3-4), 75-83.

- Oldfield, E. E., Bradford, M. A., Augarten, A. J., Cooley, E. T., Radatz, A. M., Radatz, T., & Ruark, M. D. (2022). Positive associations of soil organic matter and crop yields across a regional network of working farms. Soil Science Society of America Journal, 86(2), 384–397.

Updated: March 18, 2025

Reviewed by: Damon Smith, Erin Silva, Francisco Arriaga

Soil Health Lab, Sampling, and Test Selection Considerations

Soil Health Lab, Sampling, and Test Selection Considerations An Overview of Common Soil Health Indicators

An Overview of Common Soil Health Indicators Why Test Your Soil Health?

Why Test Your Soil Health?  BMPs of NMPs #6: On-Farm Implementation of Nutrient Management in Southwest WI

BMPs of NMPs #6: On-Farm Implementation of Nutrient Management in Southwest WI