Overview of the Farm

In 2010, Lincoln Fishman and Hilary Costa purchased Sawyer Farm, a 40 acre property nestled at 1,600 feet above sea level in the hills of Western Massachusetts. On five acres surrounded by woods and pasture, they cultivated organic storage crops such as carrots, onions, beets, and potatoes, supplying their farm store and wholesale markets year-round. Additionally, they grew hemp to support their own farm-to-bottle CBD company.

Initially, Lincoln and Hilary relied on draft horses to till their fields, integrating compost and cover crops into their practices – what they referred to as “apology practices” – to help repair the damage caused by tillage (Figure 1). However, Lincoln remained concerned about soil erosion resulting from increasingly frequent heavy rain events, particularly those brought by tropical storms in late summer and early fall (Figure 2). Given the steep slope of their vegetable field, erosion risk is high, and winter rye cover crops don’t yet offer sufficient soil protection during that vulnerable period.

Lincoln began experimenting with Dutch White clover as a strategy to improve soil health and combat erosion. This widely adapted perennial legume has a dense, shallow root system that helps protect the soil and suppress weeds. Once established, it withstands heavy field traffic and repeated mowing. In July, Lincoln would undersow Dutch White clover into his cash crops, allow it to overwinter, and then plow it down the following spring before planting a new crop. He repeated this cycle each year by reseeding the clover in July.

While the system effectively reduced soil erosion in the fall, Lincoln found the annual cycle of planting, terminating, and replanting to be inefficient and still reliant on significant soil disturbance.

“You establish it; you kill it; you establish it; you kill it; and you’re never really getting the full benefit either of nitrogen fixation or beneficial symbiosis with mycorrhizae because you’re never letting it really reach its full potential,” he explained. He began to wonder whether he could just plant directly into an established stand of Dutch White clover without terminating it at all.

So, in spring 2020, when it came time to plant cabbages, Lincoln purchased an inexpensive bulb auger bit for his cordless drill and drilled holes directly into an established stand of Dutch White clover.

During the first few weeks, the cabbages appeared to be getting overwhelmed by the clover. However, by the end of the season, they produced heads comparable in size to those grown in his traditional annual system, with no additional management required (Figure 3). That’s when Lincoln realized the true potential of the perennial system.

To share his ideas with other farmers and expand the scope of his experiments, Lincoln founded Momentum Ag, a community of farmers testing the perennial Dutch White clover living mulch system across a wide range of vegetable and row crops. Momentum Ag also facilitates other on-farm trials, all centered on a common goal: exploring and refining climate-smart practices through farmer-led experimentation. Lincoln shared early findings from grower efforts with Dutch White clover during CROVP webinars in the winters of 2022 and 2025. This case study draws on insights from those two presentations, which can be viewed in full here (2022 Webinar; 2025 Webinar), as well as recent conversations with Lincoln.

Pre-planting

Dutch White clover is commonly established using one of four methods: frost seeding into winter rye in February or March; direct seeding in the spring; undersowing into cash crops in mid-summer; or incorporating seeds into a fall sown, winter-kill cover crop mix. Lincoln establishes his Dutch White clover by undersowing it into a midsummer cash crop.

Prior to planting the cash crop, he cultivates the field multiple times to create a stale seedbed, which reduces weed pressure and helps extend the longevity of the clover stand. After planting, he continues to cultivate as needed with his tractor to suppress weeds. Following the final possible cultivation of the cash crop, typically in July, he broadcasts Dutch White clover seed into the standing crop using a chest-mounted spreader, mixing the seed with cracked corn for more even distribution. He seeds heavily, at a rate of 1 lb per 1,000 square feet (or 44 lbs per acre), which is two to four times the standard recommendation, to ensure good establishment. A final round of hand weeding or hoeing helps incorporate the seed. To promote overwintering success, Lincoln ensures seeding is completed by mid-August, as later seedings tend not to overwinter as well.

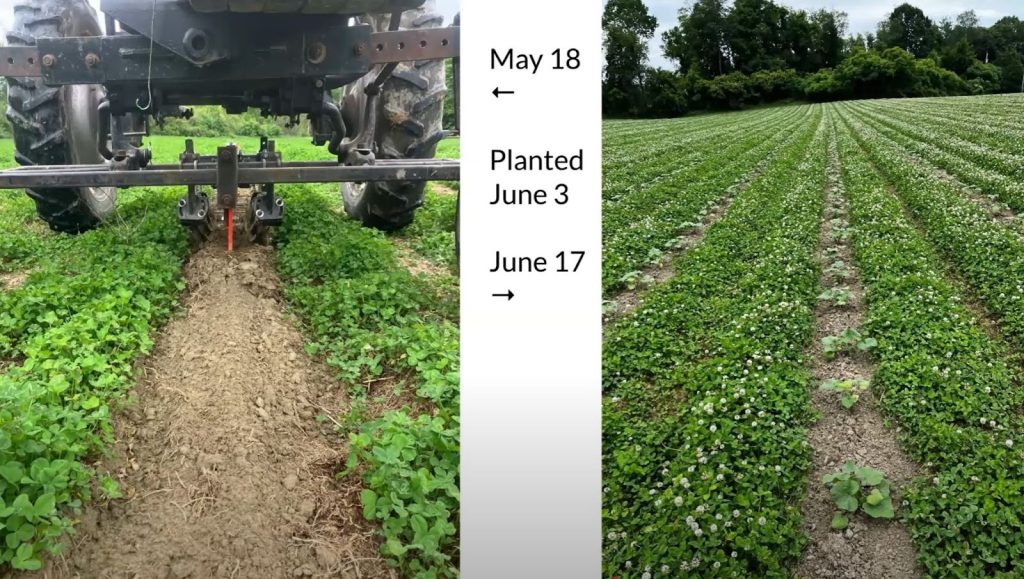

By early fall, the Dutch White clover has grown into a thick, lush stand, which resumes growth early the following spring. To establish planting zones within the living mulch, Lincoln and other growers typically use one of two methods: the “zip” or the “strip” method. As the names suggest, the primary difference lies in the width of the planting zone. The zip method involves creating a narrow slit in the clover using a series of coulters and shanks. This minimally disruptive approach allows the clover to grow right up to the base of the transplants, leaving no bare soil exposed. In contrast, the strip method involves either strip tilling or applying herbicide to a narrow band of clover along each planting row, creating a competition-free zone of bare soil for the crop. The width of the strip varies depending on available equipment for tillage, cultivation, or spraying, with a typical target width of around 12 inches.

Both the zip and strip systems offer distinct advantages and trade-offs, and certain crops tend to perform better in one system over the other. In the zip system, clover is maintained right up to the base of the plants, virtually eliminating the need for weeding. However, this close proximity can lead to reduced cash crop yields due to competition and makes transplanting more challenging, as the ripping process creates very little loose soil for good root contact. In contrast, the strip system involves creating a narrow tilled band of soil, which makes transplanting easier and provides a competition-free zone for the cash crop. However, this exposed strip also creates space for annual weeds to establish and reduces some of the key benefits of the living clover mulch, such as weed suppression, erosion control, and improved soil health. While Lincoln has focused his efforts on refining the zip system, he notes that farmers using the strip method have self-reported high success rates, making it a potentially better option for those with lower risk tolerance or less on-farm experience.

A third method trialed by a farmer in the Momentum Ag network involves transplanting cash crops into a thick layer of compost applied directly on top of the clover. The compost needs to be thick enough to suppress the clover during the critical establishment period for the transplants and must be kept consistently well-watered until the plants have developed strong root systems.

Transplanting

On transplanting day in his zip system, Lincoln begins by mowing the clover along the planting rows using a hay mower, preparing the area before creating the furrow.

He and other farmers have experimented with various equipment to create the zips and strips within the clover. Zips are typically made using a combination of sharp coulters and a narrow ripper, set to a depth of about a few inches below the root ball (Figure 4 and Figure 5). This depth is crucial to alleviate soil compaction and create some loose soil for planting. However, in lighter or sandy soils, ripping too deeply can create air pockets that interfere with the transplants’ ability to access moisture. Strips can be created using similar coulter and ripper setups, but adjusted to create a wider band. Some growers modify standard rototillers (either 3-point hitch or BCS) by removing tines to create narrow strips, while others utilize commercial strip tillers or have built their own custom strip tillers (Figure 6 and Figure 7).

Figure 6. A strip tiller with a similar coulter ripper setup as in Figure 4, but with two wavy coulters on the rear to make a wider strip. Made by Island Grown Initiative, Martha’s Vineyard, MA.

Transplanting can be done either by hand or with mechanical transplanters. Lincoln uses a carousel-style mechanical transplanter but notes that achieving good soil contact can be tricky. Alternatively, experienced tractor operators run a waterwheel transplanter over the furrow (Figure 8). Lincoln acknowledges that his mechanical transplanting method is still a work in progress and requires further experimentation to optimize.

“You need somebody on the ground who is fully focused and can make little adjustments to try to get the right kind of down pressure without smashing the transplants,” he said. “You’re also controlling the depth that the root ball is in or out of the soil, how close or far the packing wheels are, how much pressure there is down on them, how deep the shoe is running, how deep the ripper is running, how deep the coulter is running.”

“It’s a lot of work,” he acknowledged, but he maintained that transplanting accounts for the bulk of the labor throughout the growing season. “The labor flow is really different in this system than in a tillage-based system,” he explained, because there is a reduced need for weeding later on.

Growers interested in experimenting with planting into perennial Dutch White clover without investing in costly equipment can start by creating planting holes using a bulb auger attached to a battery-powered drill or a long-handled bulb transplanter – both methods Lincoln used in his early trials.

Lincoln has used transplants ranging from 128-cell plugs to 2.5-inch pots, noting that smaller transplants may require more frequent mowing of the clover during establishment. More important than size, he emphasizes, is the overall health of the transplants to ensure they can compete effectively with the clover. Unlike transplants grown in bare soil or plasticulture, which can afford to idle for a while as they recover from transplant shock or poor transplant condition – plants set into clover need to be as vigorous as possible to establish quickly.

In general, clover living mulch is best suited for larger, longer-season crops with deeper root systems. It’s also ideal for crops where a slight reduction in size or weight is not critical. For example, the system works well for cut flowers, where abundant blooms are more important than individual flower size. In fact, the added competition from the clover may even encourage the crop to accelerate its flowering cycle, an advantage in certain situations.

“Some of this is just choosing crops where it’s not the end of the world if production is down a little bit, in terms of reducing risk,” he said. “But there are plenty of cases where we’re seeing equal or higher production in clover.”

Tomatoes, hemp, cabbage, and other brassicas seem to perform particularly well in the zip system, and Lincoln has even had success direct-seeding beans (Figure 9, Figure 10, and Figure 11). Meanwhile, crops like peppers, eggplant, and squash appear to do better in the strip system. One hypothesis is that the clover limits soil warming, which affects peppers and eggplant, while squash may struggle due to nutrient competition. One of Lincoln’s ongoing goals is to deepen his understanding of how the system interacts with different cash crops.

“You need a way to manage the relationship between the clover and the cash crop so that it’s symbiotic, not antagonistic,” he explained. “And we don’t know exactly how to do that yet. There may be cases where two species just don’t play well together, and you could say, Squash doesn’t do well in zip. Or you could say, What are we missing?”

Maintenance

Once the clover stand is established and transplants are in place, perennial Dutch White clover systems require relatively little maintenance. Immediately after transplanting, Lincoln lays drip tape along each row to reduce water competition between the cash crop and clover, especially during dry years. Growers achieve the best results by irrigating aggressively – ideally with drip tape, but overhead works too – during cash crop establishment, when moisture competition is highest. Later in the season, clover transpiration will slow, and soil moisture increases in clover living mulch systems compared to bare soil.

Lincoln aims to mow as little as possible throughout the season, not only to reduce labor but also because a number of farmers have observed that clover tends to grow more aggressively after mowing, potentially increasing resource competition with the cash crop. However, an occasional well-timed mowing is necessary (Figure 12). About 7-10 days after transplanting, Lincoln mows the clover on either side of the plants to reduce photosynthetic competition.

Occasionally, another mowing is required if the clover is especially vigorous or the crop is slow to establish. Later in the season, he may mow again if annual weeds break through the clover canopy. He does not hand-weed. In the strip system, mowing is generally unnecessary if strips are 12 inches wide or greater, unless it’s used to prevent annual weeds from going to seed.

2025 trials have illustrated the importance of preparing the strips as early in the spring as possible and cultivating them several times before planting the cash crop to eliminate clover and emerging weeds. Creating a smooth, stale-bedded strip early on makes post-planting cultivation much easier, often requiring only one or two passes. The most effective cultivation setup identified so far includes two hilling discs to cut and define the strip edges, finger weeders, and spider wheels to work the area between the discs and fingers. By treating the strips like high-quality bed tops, growers can achieve significant labor savings later in the season.

There is still much to learn about fertility management in these systems. Ensuring adequate nutrients for both the clover and the cash crop is crucial. Although the clover fixes nitrogen, that nitrogen is not available to the cash crop until termination of the clover. However, Lincoln has found that the clover system reduces total fertility needs by about 25% on a per acre basis. One reason for this is that both zip and strip systems dramatically reduce nutrient leaching compared to a bare soil system. Another is that the fertilizer is applied in a narrow 12-inch band around the cash crops, rather than broadcast across the entire field. If fertilizer is spread over the whole field, including in the aisles, the clover will use the nitrogen instead of fixing its own. In zip systems, fertilizer is applied to the surface, whereas in strip systems, it can be incorporated into the soil. To avoid burning the plants, Lincoln recommends applying the fertilizer 1-2 weeks before planting if possible; otherwise, he suggests a split application. In the Dutch White clover system, it’s critical that transplants have ample nutrients at planting time for rapid establishment.

One notable exception in this nutrient management approach is sulfur. Sulfur is required for nitrogen fixation and is consistently lower in soils in Dutch White clover systems compared to bare soil systems. Since sulfur is important for the clover and cash crops, it should be broadcast rather than banded. Lincoln broadcasts calcium as well, whereas all other nutrients he applies in a narrow band.

Lincoln concedes that optimal fertilizer rates may be significantly different from farm to farm. He notes that some growers are getting great yields with zero fertilizer, while others have needed 50% or 100% of normal application. Although trials have been successful across a range of fertilizer rates, farmers who have hoped for a significant nitrogen contribution from the clover have generally been disappointed. For the moment, it seems safest to plan for typical or recommended rates. More research is needed to understand why such differences in fertility needs exist. Lincoln emphasizes the importance of annual soil testing, as nutrient cycling in this system is dynamic and differs substantially from bare soil or conventional tillage-based systems.

As the clover stand matures, perennial grasses gradually begin to move in. For Lincoln, this generally starts in the third year. By the fourth year, grasses make up about 20% of the stand. In these conditions, he was still able to grow vigorous crops like CBD hemp but wouldn’t have attempted less vigorous crops like cabbage. After this point, Lincoln plows the stand under and plants small, direct-seeded crops such as carrots, beets, alliums, or salad greens into bare soil.

Summary

The theoretical crop rotation for the perennial Dutch White clover system looks like this:

Years 1–4:

Grow cash crops directly into the clover. Begin with fussier crops, then gradually shift to more vigorous crops that can better compete with any encroaching perennial grasses. After each harvest, mow the remaining crop residue to speed up decomposition and help the clover fill in gaps. More recently, Lincoln has begun no-till drilling small grains as an overwintering cover crop into the clover post-harvest to increase system diversity and add carbon.

Year 5:

Several options are possible:

- Allow the clover to grow out as pasture or integrate grazing animals.

- Plow the stand under and plant smaller, direct-seeded crops like carrots, beets, alliums, or salad greens. Follow with a small grain cover crop after harvest.

Year 6:

Frost-seed clover into the overwintered cover crop, then move back into clover living mulch after crimping or mowing the small grain cover crop.

Within a broader context, Lincoln has begun to think of zip and strip not as distinct systems but as different points along a continuum of living aisle systems. At one extreme lies the zip system, where the planting strip is reduced to just a few inches—only enough to get the plants in the ground. In contrast, strip systems feature bed tops that can range from 12 inches to 5 feet. As Lincoln explains, it ultimately comes down to the proportion of the field dedicated to living mulch versus the portion used for planting. Across all living aisle systems, including both zip and strip, the core management challenges remain consistent: mowing and edge maintenance.

At this point, Lincoln can confidently say that nearly every cash crop can thrive in strips 12 inches wide or more, provided they’re well managed. He’s far less certain about zip systems. While he and other growers have achieved notable success with some zip trials, others have failed, and he doesn’t fully understand why. Lincoln suspects that soil characteristics and microbial activity play major roles in determining success, but no consistent patterns have yet emerged from the data. “It may have to do with a kind of deep biological complexity that will take a long, long time to capture through soil analysis,” he admits, though he remains hopeful. For growers interested in experimenting with living aisle systems, Lincoln recommends starting with strip systems while testing a few rows of zip to see how they perform.

While the clover living mulch system is showing strong promise in the Northeast and Upper Midwest, many questions remain. Can the number of post-planting mowings be reduced through timely, repeated mowings before planting? Is there equipment that could undercut the clover sod to temporarily suppress it while transplants establish? Are there mechanical transplanters that function effectively in the zip system? How can growers ensure good soil contact during transplanting? How do untested crops perform in this system? What are the fertility requirements for different crop species, especially as the clover stand ages? And what strategies can reduce yield drag on cash crops?

These are the kinds of questions farmers are working to answer through on-farm trials with Momentum Ag.

Conclusion

Reflecting on these questions, and others that have emerged through ongoing experimentation, Lincoln pointed to a satellite image of Almería, Spain, where vast expanses of farmland are covered in white plastic (Figure 13).

Figure 13: Plastic greenhouses surrounding El Ejido, in the Spanish province of Almería, captured by NASA’s Landsat 9 (NASA Earth Observatory, public domain)

“I like to think that whoever came up with this idea in the 1950s, people probably said, You’re crazy. Plastic is never going to be cheap enough. You’d need to develop equipment to lay it down over acres and acres. You’d have to make holes in it to transplant through. You’d need a whole new machine to do that…I think we can feel trapped by the options that currently exist for us. But, there’s going to be something better, and we need to keep our eyes on the prize. I don’t know if it’s going to be this clover thing or not, but I think it’s in the zone of ideas that are exciting enough. There are all these problems – maybe the equipment doesn’t exist yet – but it’s not hard to imagine. Anything good that we come up with will feel like that: it’ll feel like too heavy of a lift.”

But,” he said, “everything was like that in the beginning.”

Momentum is always adding to its network, and you can get in touch at hello@momentumag.org. (We should note that Lincoln is full time at Momentum Ag now and Sawyer Farm is in the process of transitioning to new farm owners.)