Introduction

From 2006 to 2010, Wisconsin averaged 282,000 acres of harvested wheat (USDA-NASS, 2007-2011). After harvest some of these fields are planted with late summer alfalfa and a few more receive manure, but many sit fallow for the rest of the growing season. Fields that are tilled late summer to control weeds are left vulnerable to erosion. If farmers take action after harvesting wheat or other small grains, they can utilize the approximately 40% of growing season precipitation and Growing Degree Units (GDUs) that remains as of July 31st (NOAA, 2004). This 40% rule of thumb applies throughout the state. Planting timing is important because 20% of annual GDUs accumulate in August. On average between the end of July to the end of October, Wisconsin receives 975 to 1,300 GDUs (corn base) and nine to eleven inches of precipitation. This amount of heat and precipitation leaves the potential to grow more forage.

A new strategy in Wisconsin for building forage inventories is to raise double crop forages after small grain harvest. Double crop forage is a sound strategy in Wisconsin because of the need to store large forage inventories for winter. Rather than growing emergency forages to build inventory during weather stressed years, planned double crop forage can increase the likelihood of success.

What are double crop forage options?

A wide range of forage crops potentially can be planted after small grain harvest, however weather conditions will influence which forages will be more successful. Double crop forages such as brassicas, small grains, ryegrass, legumes, sorghums and millets, and even corn silage can be sources of late season forage. Many studies have been conducted on emergency forages and fall small grain forage. Yield results vary from 0.5 tons of dry matter per acre to 4.0 tons of dry matter per acre or more in Wisconsin (Undersander, 2008).

Which double crop forages are most likely to perform well?

The most well understood double crop forage option is planting fall oats near August 1st. Two Focus on Forage issues by Coblentz and Bertram from 2012 explain the yield and quality characteristics of fall planted oats. Research demonstrated oat variety selection is important for maximizing yield and quality. For example, Forage Plus oat is a good fit for yield and quality reasons because this variety should not develop into the boot stage as quickly as others thereby allowing time to work around corn and soybean harvest. Earlier maturing oat varieties can yield well but forage quality may decrease as heading stage is reached. If fall planting is delayed, then earlier maturing varieties should be considered. Adding peas to oats can increase protein by 3 to 5%.

On farms that use grazing, forage brassicas such as forage radish, turnip, kale or swedes have potential because they are fast growing and high quality. With recommended planting dates from mid-July to late August, timing of brassicas aligns well after small grain harvest. Grazing brassicas can create unexpected livestock disorders such as bloat or nitrate poisoning. It is important to avoid abrupt changes from poor quality pasture to brassicas and continue to supplement dry hay (Undersander, 1996).

Are there unique double crop forages?

One unique approach to double cropping is the potential to frost seed red clover into an existing wheat stand in spring. This practice typically is done to establish the nitrogen fixing cover crop in order to reduce fertilizer expenses the following year. However, given a timely wheat harvest and a warm August, red clover’s fall growth may be sufficient to justify harvesting. Research by Stute and Shelly measured 1.7 tons of dry matter per acre with a range of 0.33 to 3.26 tons of dry matter per acre for red clover growth after wheat harvest. Be aware that some springs do not provide the right freeze-thaw conditions for frost seeding. Since it is unlikely red clover will dry for hay in the fall, plan to harvest it as haylage. If red clover is grazed or green chopped, watch out for bloat. Warm season grasses including sorghum, sudangrass, sorghum sudangrass, millets, and corn silage are riskier double crop forages. These options have the highest probability of success when small grains are harvested early and temperatures are above average. Soil dryness during midsummer may be a deterrent to planting these crops. Delaying planting past mid-July and/or cool temperatures will significantly hinder yield of these crops. Sorghum, sudangrass, sorghum sudangrass and millet typically have lower forage quality than common Wisconsin forages. If forage quality is a high priority, selecting BMR varieties may help improve forage quality.

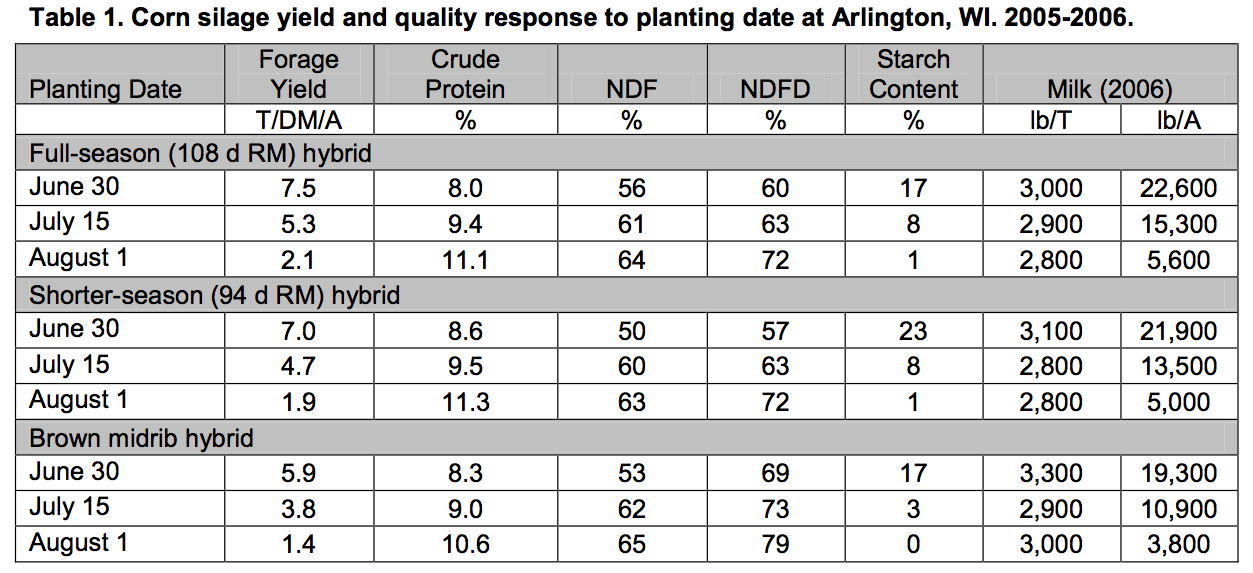

Another warm season grass to consider is planting corn silage after small grain harvest. Again, weather conditions will influence the success of this practice. University of Wisconsin corn silage planting date studies at Arlington, WI (Table 1) have demonstrated a yield of 3.8 to 5.3 tons of dry matter per acre of low starch silage when planted on July 15th (Lauer, 2008).

Can there be problems?

Before raising unfamiliar forages, it is important to consult with the farm’s nutritionist to ensure adequate quality feed can be grown for the intended diet. Fall grown forages may have different quality characteristics from spring planted equivalents. For example, late planted corn silage will have low starch content if the ear is undeveloped at harvest. Species such as sorghums, sudangrass and millets have feed characteristics that are less ideal for milking dairy cows. If harvest is delayed into late fall; frost, lack of field drying, or even mud can become harvest problems. Access to a bagger or bale wrapper will provide the opportunity to segregate these alternative forages allowing for better use in a ration.

Farmers and agronomists planning to integrate double crop forages into the crop rotation are advised to look back at the field’s herbicide history. There may have been herbicides sprayed within past years that can create herbicide injury from persistence, plus feeding forage from fields with these residues may be an off-label use (Davis, 2012). Since some double crop forage species are not commonly found on herbicide labels, the field may need to follow the longest rotation interval provided. Review herbicide planting restriction intervals to select products that will allow for the necessary flexibility.

Plan seed acquisition early, yet have flexibility. Because of the limited use of double crop forages in the past, local seed suppliers may not have all seed immediately available in local warehouses. While it is important to plan seed purchases early, variability of summer weather may change planting decisions.

Planting double crop forages after small grains, such as winter wheat, is a strategy to utilize more of the growing season to build winter feed inventories. Be aware of the yield and quality characteristics of the forage plus potential complications that come with double cropping.

References

Coblentz, W., and M. Bertram. 2012. Fall-Grown Oat Forages: Cultivars, Planting Dates, and Expected Yields. Focus on Forage. Vol.14, No. 3. University of Wisconsin Board of Regents. Madison, WI.

Coblentz, W., and M. Bertram. 2012. Fall-Grown Oat Forages: Unique Quality Characteristics. Focus on Forage. Vol.14, No. 4. University of Wisconsin Board of Regents. Madison, WI.

Davis, V. M., 2012. Is it legal to use a cover crop as a forage crop? Maybe NOT…… University of Wisconsin Extension. Madison, WI.

Lauer, J., 2008. Planting Corn in June and July! What can you expect? Agronomy Advice June 2008. University of Wisconsin Board of Regents. Madison, WI.

NOAA, Nation Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 2004. Climatology of the United States No. 20. Monthly Station Climate Summaries, 1971-2000. Wisconsin. Asheville, NC.

Stute, J., K. Shelley. Frost Seeding Red Clover in Winter Wheat. University of Wisconsin Extension. Madison, WI.

Undersander, D., 1996. Use of Brassica Crops in Grazing Systems. University of Wisconsin Extension. Madison, WI.

Undersander, D., 2003. Sorghums, Sudangrasses, and Sorghum Sudangrass Hybrids. Focus on Forage Vol. 5 No. 5, University of Wisconsin Board of Regents. Madison, WI.

Undersander, D, D. Holen, P. Peterson, M. Endres, R.Leep, P. Holman, M. Bertram, V. Crary, C.Scheaffer, 2008. Emergency Forage. University of Wisconsin Extension. Madison, WI.

USDA-NASS, United States Department of Agriculture National Statistics Service. 2007-2011. Wisconsin Agricultural Statistics Summary. Madison, WI.