Most graziers value pasturing their livestock because these systems work with ruminants’ natural behaviors and herd instincts, reducing stress for both the handler and the animal. However, there are times when graziers need to work with livestock on the farmers’ terms, pushing the limits of the animals’ comfort zone. Moving animals to an unfamiliar area, sorting animals for weaning, corralling animals for health checks, or loading animals onto a trailer are all normal activities for a grazing operation that put pressure on livestock. While everyday grazing activities may be the most enjoyable part of managing a grazing operation, these less routine animal handling activities may be an obstacle to the overall success or enjoyment of the operation if basic animal handling skills and facilities are lacking.

Big Picture

Livestock handling has the potential to make or break a grazing operation. So, developing good stockmanship skills and thoughtfully designing grazing infrastructure (fences, lanes, water, etc.) to accommodate low stress animal handling should be a top priority for each farm. This process takes time and patience. While effective livestock handling requires some initial investment in basic equipment such as a squeeze chute, significant investments in handling facilities should be made incrementally as farmers learn the above principles to avoid the costly mistake of building facilities that are not effective.

Key Principles of Effective Cattle Handling in Grazing Systems

Livestock handling has the potential to make or break a grazing operation – can be the difference between success or failure.

Effective livestock handling requires investment in some basic equipment but does not necessarily require significant investment in facilties.

The biggest “investment” to develop effective livestock handling should be time to learn stockmanship and animal behavior on a farm.

Low Stress Livestock Handling

Low Stress Livestock Handling is a livestock-centered, behaviorally appropriate, physiologically oriented, ethical and humane method of working livestock based on mutual communication and understanding between the farmer and animal (Whit Hibbard – Stockmanship Journal).

Low stress livestock handling involves three elements: understanding livestock behavior, using your actions to manage the livestock, and having infrastructure that facilitates both.

Understanding Animal Behavior

Every class of livestock has known behavior patterns based on their species’ historic adaptation to their environment. Some of these behaviors are genetically dictated by the animals’ physiology, others are learned from their mothers and the herds they grow up in. Successful livestock handling starts with a basic understanding of these behaviors:

1: Understand Ruminant Mentality

Most ruminants are prey animals with a herd mentality. They are programmed to avoid perceived threats and seek the protection of the herd. Successful handling of your animals must involve minimizing pressure and threats and maintaining a safe, comfortable herd environment. You, as their handler, are perceived as a threat. Using that knowledge allows us to move and handle animals as we need to.

2: Understand Cattle Senses

Cattle and most other ruminants have nearly panoramic vision and can see 300 degrees, compared to 180 degrees for humans. They have a blind spot directly behind them. Because their eyes are on the sides of their faces, they have poor depth perception, and a shadow on the ground may appear as a hole.

They also have poor sound isolation, so they have difficulty determining where noises are coming from. Because of these limitations and their prey mentality, livestock tend to be cautious and leery. To further complicate matters, cattle have an acute sense of smell. They can smell an animal in heat from a significant distance and react strongly to the smell of blood. They pick up on fear and stress in other animals, partly due to detection of hormonal changes.

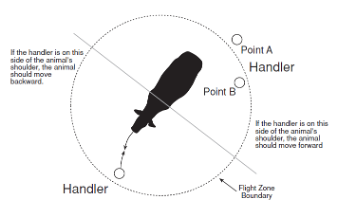

3: Use the Flight Zone

Flight zones can be thought of as “personal space.” When a predator (person) approaches within that zone (Figure 2), stress increases and the animal will likely move away. Flight zone radius is similar for cattle, sheep, and pigs, but varies significantly among individual animals.

The flight zone is approximately 5-25 ft for tame animals and up to 300 ft for wild animals. Extremely tame animals may have little or no flight zone, making them hard to manage in some situations.

4: Use the Response to Pressure

There is a “point of balance” for each animal that, when crossed by a handler within the flight zone, will cause the animal to move in the opposite direction. This is a primary tool for making animals move in the direction you want them to go.

Gathering Livestock for Handling

What are essential stockmanship skills?

Being able to anticipate how animals’ behavioral tendencies allow the handler to apply pressure – livestock logic – is critical to effectively moving animals or herds where you want them to go. While an animal’s behavior is largely inherent, the environment of each farm will strongly influence how that behavior manifests itself. Understanding likely inherent responses can allow a grazier to create an environment with limited threats and obstacles for orderly animal movement.

5: Anticipate Movements

Anticipate where animals will naturally want to go when they are pressured. When you start a herd or individual animal moving, they will respond by moving toward a location of safety or familiarity. If animals are winter housed in a building, they may move in that direction. Separate groups of animals will always move toward each other, not away, and animals separated from a larger group will grow more uncomfortable the further away they get.

6: Identify and Block Escape Routes

Lay out a direct route to where you want the animal(s) to go. Make sure there are no dark places or foreign objects that cause fear. Areas or objects that animals perceive as unfamiliar or threatening can disrupt movement by causing animals to stop and balk.

This farm-specific information should be applied with these measures to keep livestock flowing toward a handling facility:

7: Create Clear, Obvious Paths

Always present animals clear, obvious paths forward, moving toward light and avoiding dark places. Once they are moving in a specific direction, they will keep moving if they can see a clear way forward.

8: Work at the Animals’ Pace

Allowing them to choose when to move as you pressure them may take a little more time, but results in a calm, more orderly move. Too much pressure can cause them to turn and go back where they came from. Similarly, too little pressure may have the same result as an unclear direction may cause them to return to where they were comfortable.

9: Always Remain Visible to Animals

Maintain a calm voice and controlled body movements. Rapid movement or loud shouts can startle animals and cause panic.

10: Catch Animals Before They Know They’re Caught

Before “fight or flight” instincts are triggered, or any type of threat is detected. This can be achieved by working them near where they are currently grazing, keeping them near their herdmates or utilizing portable facilities.

Handling Livestock

What are essential working facilities?

Managed grazing infrastructure that is versatile, adaptive, and scale and budget-appropriate is key to an effective managed-grazing system (see our fact sheet 15 Tips for Designing Fencing Systems for Managed Grazing). Livestock handling infrastructure is integral to this system. While handling facility needs may be minimal, there are some basic design elements that facilitate low-stress handling.

11: Access a Squeeze Chute

A means of restraining an animal for veterinary treatment, most commonly a squeeze chute (Figure 4), is a necessity. These not only keep the animals safe, but they also keep the animal handlers, veterinarians, reproductive technicians, and others safe. Most producers install a stationary chute in a permanent handling area for this purpose, but portable chutes are available to purchase or rent.

12: Train Animals to Respect Temporary Electric Fencing

Temporary electric fencing can be used for most animal movement. In most cases, permanent lanes are not necessary, and temporary lanes can be set up with polywire and used to move animals into handling facilities.

13: Utilize Portable Handling Facilities When Possible

Low-cost options are available and can reduce logistical challenges if individual animals need to be sorted from the herd when it is far from the farmstead. A corral can be set up near the herd, and animals (Figure 5) can be caught before they know they’re caught in close proximity to their herdmates.

14: Design for Loading Animals

Facilities should be designed to easily load animals onto a trailer, especially for operations that sell breeding stock or process animals for meat frequently.

15: Design for Corraling and Sorting Animals

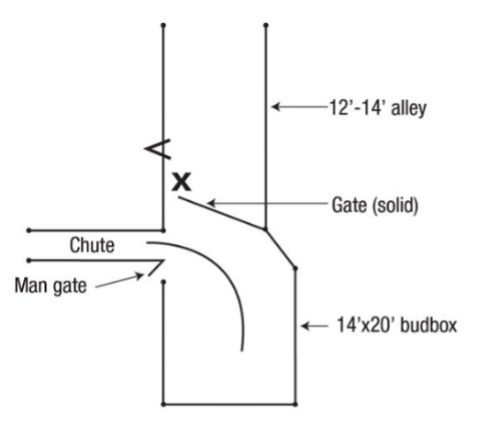

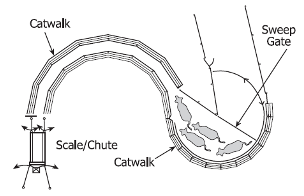

There are several design concepts to achieve this. Commercially designed systems can be very expensive, but a handling system can be easily constructed with affordable materials. Common designs include the Bud Box and sweep tubs (Figures 6 & 7). Key elements include having multiple pens that allow the producer to sort individual animals from the herd and move unwanted animals out of the handling area, including an alleyway that funnels the animals individually into the chute, and ensuring the animal has a clear view of what’s pressuring them and the animal in front of them.

Authors:

Jason Cavadini, Grazing Outreach Specialist, UW–Madison Extension

Laura Paine, Grazing Outreach Coordinator, UW–Madison Extension

Adam Abel, Grazing Specialist, USDA-Natural Resources Conservation Service

Last Updated: January 7, 2026