Introduction

Sweet corn is enjoyed by people across the United States. Some sweet corn is harvested and sold directly to the consumer (i.e. corn on the cob). The rest of the sweet corn is processed, packaged and/or combined with other food products through a processor.

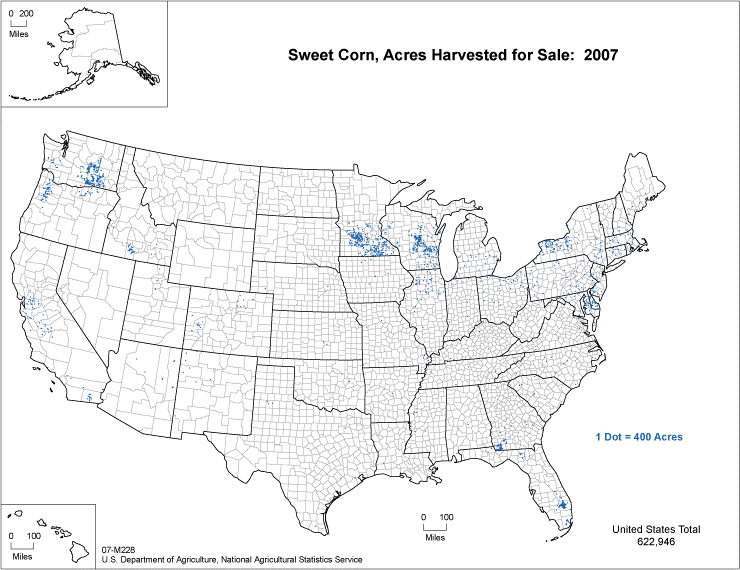

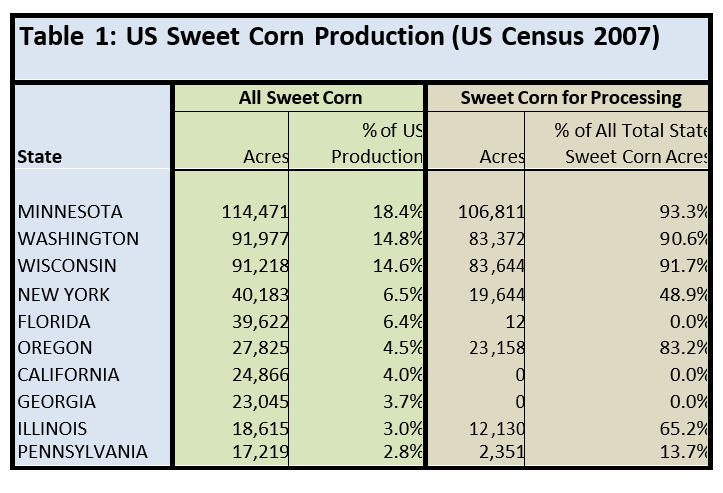

The production of sweet corn is concentrated in certain parts of the United States (see map below). The top three states (Minnesota, Washington, and Wisconsin) contain 47.8% of all acres harvested as sweet corn. (Table 1). These three states send over 90% of sweet corn acres to a processor. Of the top ten states that harvest sweet corn in the US, three states (Florida, California and Georgia) send almost all their production directly to the consumer (no processor).

Sweet corn production produces byproducts that can be fed to livestock. They include sweet corn stalks (stalklage left on the field after harvest), sweet corn silage (from bypassed acres that were not harvested), and corn canning factory waste (sweet corn waste).

This fact sheet will deal exclusively with the sweet corn waste.

What are the physical characteristics of sweet corn waste?

When sweet corn is harvested, the entire ear with husk is harvested. At the processing facility, the corn kernels are removed. The remaining portion is the sweet corn waste (SCW). It will contain tops of plants, husks, cobs, culled ears, and some kernels. The amount of each in the SCW will depend on the processing equipment, corn variety and maturity, growing conditions for the sweet corn, and equipment operators.

In Wisconsin, a lot of the SCW is fed to cattle. Some processors will store the SCW and resell at a later time. Other processors send SCW directly to farms (often through an intermediary contractor). Low dry matter content (20-25%) and physical characteristics can make it more challenging to store than traditional corn silage. It also can lead to a high volume of leachate; the storage sites of SCW for more than 150 tons must meet specific design requirements including the collection of leachate (WI DNR – Administrative Code NR 213.13). Another challenge of SCW is the physical form. SCW is not run through a forage harvester like corn silage and therefore contains leaves/husks that are about a foot long. These long pieces make the SCW stringy, fluffy, and difficult to pack well in a bunker.

What are the feeding characteristics of sweet corn waste?

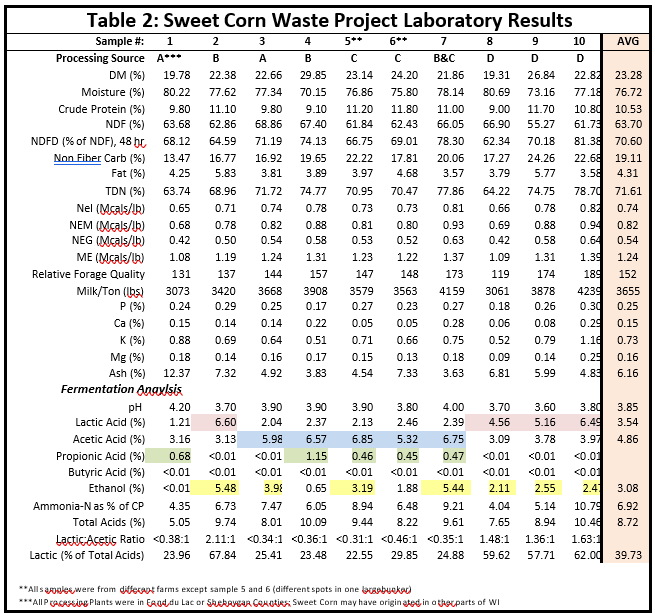

Laboratory analyses and management recommendations for SCW are limited. In order to better understand the feed value of SCW and to develop management recommendations for using SCW as a livestock feed ingredient, a small project was undertaken. Samples from nine farms (10 samples) were collected in February of 2009. They were analyzed by the UW Soil and Forage Analysis Laboratory in Marshfield, WI. Samples were analyzed using wet chemistry and summarized in Table 2.

The lab analyses of the samples were variable. Dry matter ranged from 19.8% to 29.9%. Major chemical analyses (protein, carbohydrate, fat and mineral components) showed this same variability.

What fermentation products are present in sweet corn waste?

The fermentation analysis shows a high level (>3%) of acetic acid in all the SCW samples; samples 3 through have levels above 5%. Typical acetic acid levels in corn silage would range from 1.0 to 1.5%. According to Dr. Richard Muck, US Dairy Forage Research Center, the presence of propionic acid in half of the samples together with elevated acetic and no butyric acid definitely suggests naturally occurring Lactobacillus buchneri plus Lactobacillus diolivorans. The L. buchneri produce 1,2-propanediol and acetic acid from consuming lactic acid. The L. diolivorans convert the 1,2-propanediol to propionic acid.

The fermentation analysis also shows elevated levels of ethanol in all but two of the samples. Normal ethanol levels in corn silage are about 1%. Fermentative yeasts may be using sugar left after fermentation; these yeasts would have the ability to grow in low pH. This fermentation would occur after lactic acid bacteria fermentation but before L. buchneri have developed.

What are the implications for feeding dairy cattle?

Based on the results of these analysis, recommendations for feeding SCW to dairy animals are as follows:

- The variability in the lab analyses point to the need to test and monitor SCW just as nutritionists have monitored other fermented forage

- Fermentation byproducts should be monitored in addition to standard chemical

- High levels of acetic and ethanol may be a concern in SCW if the feeding rates are significant or the feeding group is sensitive to these compounds

- Farmers purchasing SCW from outside sources should be sensitive to variation in this

- Prices paid for SCW should be adjusted for quality if possible.

- When SCW is purchased at harvest time, dairy producers should be prepared to feed SCW to non-critical, less sensitive groups such as heifer or far-off dry cows. If the SCW goes through a fermentation cycle that results in high ethanol or acetic acid levels, the forage may not be suitable for transition dairy cows (around calving) and high producing dairy cows.

How should sweet corn waste be managed?

Phone calls were made to farms involved in the survey to ascertain potential differences in the fermentation analysis between samples. The SCW in this survey came from four different processing plants in eastern Wisconsin. The sweet corn processed may be local to these plants or come from other parts of the state.

All farms indicated that they did not use any bacterial inoculants or chemical preservatives (no information was available for sample 2). Three farms (Sample 3, 7, 10) layered their SCW underneath corn silage (Picture 2). The SCW from all samples was stored in either a bunker or pile.

Anecdotal information on packing practices seemed to be the most intriguing (Table 3). Three out of four producers with SCW that had the highest levels of acetic acid indicated the SCW was not packed at all or not packed well. Four out of the five producers with SCW that had lower acetic acid levels insisted they packed well and often (the other producer purchased SCW offsite and was not knowledgeable of how it was packed). All producers pointed out the fact that SCW is difficult to pack.

The farmer comments point to the idea that packing likely plays an important role in how the SCW ferments. The presence of oxygen and secondary fermentation processes seems to influence the fermentation analysis. Producers will need to evaluate the economics of packing inexpensive SCW and the potential benefits.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to the producers for allowing the sampling of the SCW and UWEX Forage Team for the funds for laboratory analysis.

▶ Watch: Focus on Forage Management

▶ Watch: Focus on Forage Management ▶️ Watch: From Field to Feed: What We Know about Growing High Oleic Soybeans

▶️ Watch: From Field to Feed: What We Know about Growing High Oleic Soybeans ▶ AI in Agriculture

▶ AI in Agriculture ▶ Evaluating MRTN Rates for Corn Grain and Silage After Manure Application

▶ Evaluating MRTN Rates for Corn Grain and Silage After Manure Application