Are there differences in soil health indicators between higher and lower yielding cranberry beds in Wisconsin?

What we did

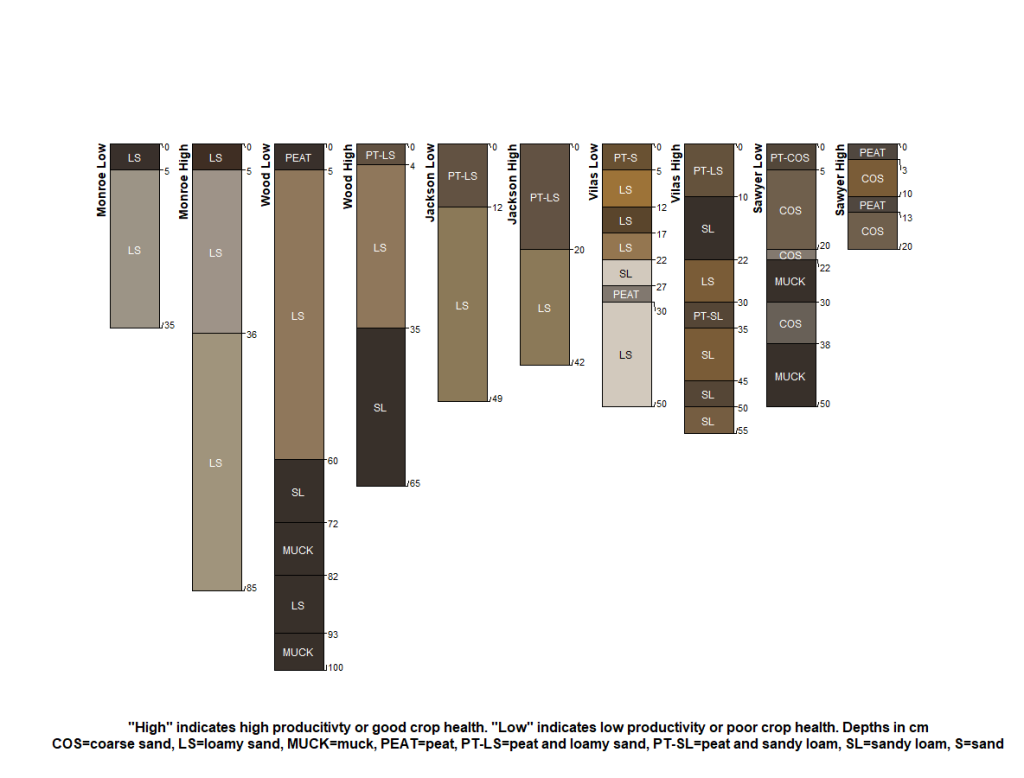

Sampled surface soils (top 6”) from one higher and one lower yielding cranberry bed on four farms in Jackson, Monroe, Sawyer, and Wood Counties, Wisconsin in summer of 2022. Higher and lower yielding beds were self-identified by growers at each farm. All beds were sandy, of similar age, contained the same cranberry variety, and were managed similarly.

Analyzed soil samples for soil fertility (pH, cation exchange capacity (CEC), plant available macro and micronutrients), and indicators of soil health (soil organic matter, potentially mineralizable nitrogen (PMN), permanganate oxidizable carbon (PoxC), and phospholipid fatty acids (PLFA)).

What we found

When comparing higher to lower yielding beds:

- Evaluated soil health indicators were statistically similar. This means measured soil health indicators were likely not the main driver of cranberry yield differences in the evaluated beds and farms.

- Potentially mineralizable nitrogen was trending towards being higher in lower yielding beds. This means that by sampling additional farms, the data may show increased potential for naturally cycled soil nitrogen to negatively influence bed productivity.

When comparing farm to farm:

- Many traditional soil fertility measurements were significantly different. This means differences in on-farm nutrient management practices likely contributed to highly variable soil fertility levels and potentially, yields between farms.

- Microbial populations, as measured by PLFA, were statistically similar. This means soil biology in sampled cranberry beds was less influenced by management practices than the measured soil fertility parameters.

Future work

Sampling of additional farms will better define potential soil health indicators appropriate for cranberry production.

Continued evaluation of soil health indicators, particularly physical and hydrological properties, such as percent pore space, water percolation rates, and soil moisture retention, may identify specific soil health indicators reflective of cranberry bed yield differences.

Methods and statistical analysis

Soil fertility and soil organic matter analyses were run at a commercial laboratory using Wisconsin certified methodology. PLFA analyses were conducted at the Uni-versity of Missouri Soil Health Assessment Center. PoxC and PMN were run at the Arriaga Lab at UW-Madison.

Analysis of variance was performed between the higher and lower yielding beds for soil fertility and PLFA indicators using farms as block. Means of specific indicators were considered significantly different when p-values were less than 0.10.

Results, discussion, and conclusion

There were no statistically significant differences between the measured soil health indicators (Tables 1 and 2). However, there was a strong trend of greater potential mineralizable nitrogen (p-value = 0.155) in lower versus higher yielding beds (Table 1). The lack of significance between higher and lower yielding beds can be attributed to large differences in indicator results between farms. For example, for most soil fertility parameters, variability between farms contributed more than bed productivity rating (0.0069 versus 0.468, respectively) to measured indicator differences. There were significant differences between farms for CEC (0.059), copper (0.053), zinc (0.015), manganese (0.011), calcium (0.071), potassium (0.007), phosphorus (0.020), and soil organic matter (0.046). Similarly, there were strong trends indicating differences between farms for magnesium (0.116), iron (0.119), and potentially mineralizable nitrogen (0.184). Differences in soil fertility indicators between farms were generally greater than for measured microbial populations. Only arbuscular mycorrhizae fungi (0.221) had a strong trend towards differences between farms.

Soil fertility appears to contribute more to the overall soil health/property differences between higher and lower yielding beds than soil biological parameters. Potential mineralizable nitrogen contributions appear to potentially influence productivity. However, results suggest soil fertility contributions may not be related to differences in soil organic matter, as there was no significant difference in organic matter content between bed types. A larger sample pool to include more farms would increase the sensitivity to detect differences between soil health indicators and reduce the statistical variability between farms. Continuing analysis of additional soil physical and hydrological parameters may produce results reflective of cranberry bed productivity differences.

Table 1. Soil health indicator

mean values between lower

and higher yielding cran-

berry beds and associated

probability significance value

(p-value).

Table 2. Mean values of phospholipid fatty acids (PLFA)

indicators of lower and higher yielding cranberry beds

and associated probability significance value (p-value).

Authors and Funding

Francisco Arriaga and Allison Jonjak, UW-Madison, Division of Extension; Jamie Patton and Andy Paolucci, USDA-NRCS. This project was funded by Wisconsin SARE.

Appendix

Field Notes Episode 13: Agroforestry

Field Notes Episode 13: Agroforestry Establishing silvopasture in existing woodland

Establishing silvopasture in existing woodland  Establishing silvopasture by planting trees

Establishing silvopasture by planting trees The Cutting Edge Podcast Episode 6: Prairie STRIPS

The Cutting Edge Podcast Episode 6: Prairie STRIPS