Slugs are becoming an increasingly challenging pest for Wisconsin farmers who use conservation cropping practices like no-till and cover crops. The increased adoption of these practices in recent years, along with milder winters and wetter springs projected for Wisconsin in the future, may increase the importance of slugs as pests of field crops.

What are slugs?

Slugs are molluscs, a group that also includes snails, scallops, squids, and octopi. Importantly, slugs are not insects. The gray garden slug (Deroceras reticulatum) (Photo 1) is the most common slug pest in Wisconsin field crops. Scouting for slugs in field crops has also revealed the presence of the orange-banded Arion (Arion fasciatus) (Photo 2). Slugs feed on a variety of plants and can be serious pests in field crops like corn, soybeans, and alfalfa. They can be particularly problematic in fields that use no-till or reduced-tillage and cover crops1. These practices minimally disturb the soil and leave heavy residue in the field, providing a cool, dark, moist, and stable microclimate that is an ideal habitat for slugs.

What do slugs look like?

Slugs are legless, soft-bodied, and oblong. They are essentially snails without a shell. They have four tentacles on their head. The longer, upper pair of tentacles are used for seeing and smelling. The smaller, lower pair are used for feeling and tasting. Their body is covered with a slimy mucus, and they leave a characteristic slime trail wherever they go. The slime assists with movement and is a defensive measure to remove toxins or unwanted materials from their body. Their size varies depending on their species, with gray garden slugs reaching around 2 inches. Juvenile slugs resemble miniature adults. Slug eggs are small, white/translucent gelatinous spheres and are typically found under residue or in cavities near the soil surface (Photo 3).

What are the life cycle and biology of slugs?

Slugs are hermaphrodites, meaning they possess both male and female reproductive organs, but they typically mate with one another to reproduce. Mating, egg-laying, hatching, and development are not synchronized, meaning slugs are found at various stages of development throughout the year1.

Slugs have four growth stages: egg, neonate, juvenile, and adult (Figure 1). Eggs typically hatch in early spring. Neonates primarily feed on algae and fungi. They progress quickly to juveniles who feed on plants. Increased feeding occurs as the slugs mature. Juveniles and adults can remain active throughout summer if conditions allow, but they typically rest (aestivate) under hot, dry conditions. Juveniles reach maturity in the late summer to early fall. Adults then feed, mate, and lay eggs (Photo 3). A gray field slug adult can lay from 300 to 500 eggs during its lifetime. Slugs can live for about 12 months, sometimes longer, and will die shortly after laying eggs. Slugs typically overwinter in the egg stage, but mild winters can allow adults and juveniles to survive1.

In general, slugs are most active from April to June and September to October. Slugs are nocturnal, typically feeding from dusk to dawn. They may also feed during rainy or overcast days. During the day, slugs hide in soil crevices and under crop residue, which is why reduced- and no-till fields are at greater risk for damage (Photo 4). They prefer high humidity and temperatures below 70°F1. Slug populations are expected to be large and problematic during a wet spring following a mild winter, or any spring after a wet fall.

What are the symptoms of slug damage?

Slugs feed using their “rasp-like” mouthparts (called radula) to scrape the surface of plants. They can impact the seeds or seedlings. In corn, slugs scrape the leaves leaving window-pane damage, then ragged/shredded holes (Photo 5-6). In soybeans, slugs make holes in the cotyledons, then ragged holes on leaves (Photos 7-8)1.

Slugs are particularly problematic if they destroy the exposed growing point on soybeans, leading to plant death and a greater chance of stand loss. Slug damage to corn can cause defoliation, but young plants have a good chance to recover because the growing point is underground. Slug feeding injury can be confused with other pest damage, like early season black cutworm damage (Photo 9) or feeding damage by adult corn rootworm beetles (Photo 10), so look for slugs in residue below the plant and characteristic slime trails (Photo 11) to correctly identify the culprit.

Ensuring that the furrow or slot is closed during planting helps mitigate damage to seeds and seedlings. Otherwise, slugs have a dark, cool “highway” to travel from seed to seed. If the plants are small enough– have less than 5 leaves– the slugs may destroy it entirely.

How do you scout for slugs?

Economic thresholds have not been established to guide slug control in field crops. Still, scouting can help identify areas with large slug populations and fields at risk. Priority should be given to no-till fields with heavy surface residue and fields with a history of slug problems. Since slug feeding is most damaging to seeds and seedlings, you should scout for slugs immediately after planting and emergence. In tilled fields, scouting efforts should focus on areas that are most likely to provide good slug habitat, such as wet, low-lying or weedy parts of fields.

One easy, cost-effective method for slug scouting is using refuge traps1. A refuge trap is a shelter that sits on the soil’s surface and provides a moist environment for slugs to hide during the day. Traps can be made from roofing shingles, plywood boards, or cardboard. Slugs monitoring programs in Pennsylvania3 and Ohio4 use roofing shingles because they hold up well to field operations (e.g., being run over by a tractor). Refuge traps should be placed flat on the soil surface after planting the crop. Move aside residue and flag the traps so you can find them later. The number and distribution of shingles will depend on the field. In Pennsylvania, the monitoring program strives for 10 shingles per field. Monitor the traps once a week by flipping the shingle trap over and counting the number of slugs. Because slugs are active at night, the best time to check refuge traps is in the morning or at dusk. The monitoring program in Ohio recommends monitoring for 6 weeks after planting. Consistently finding slugs on the refuge traps indicates an at-risk field that should be monitored for crop damage.

Other slug scouting methods involve soil traps or pitfall traps2,5. To create a soil trap, start by digging holes 4 inches wide and 6 inches deep around the field and covering them in shingles wrapped in tinfoil. The shingles can be secured with galvanized tent stakes in opposing corners. This creates a moist environment that the slugs will seek shelter in during the day. After several days have passed, check the holes for slugs (Photo 12). Be sure to look closely for juveniles as they can be very small.

Pitfall traps are similar to soil traps, but a small plastic cup is placed inside the hole to capture pests. Containers should be placed in holes so that the rim is flush with the soil surface. Fill the container approximately halfway with water and a drop of dish detergent. The dish detergent reduces the water surface tension so slugs will sink and become trapped in the container. Secure a shingle over the pitfall trap to create a modified refuge trap. Check the container for slugs. The pitfall trap should be emptied and refilled weekly.

What is the threshold to reach for slug treatment?

Economic thresholds have not been established to guide slug control in field crops, but there are some useful guideposts. If using the refuge trap scouting method, specialists from Penn State University recommend considering a rescue treatment with baits (see chemical control section below) if there is an average of 1-2 slugs per trap and significant feeding damage/dying seedlings3. If using soil or pitfall traps, guidelines from Cornell University indicate that control may be warranted if there are five slugs per hole and the crop plant has five leaves or less5.

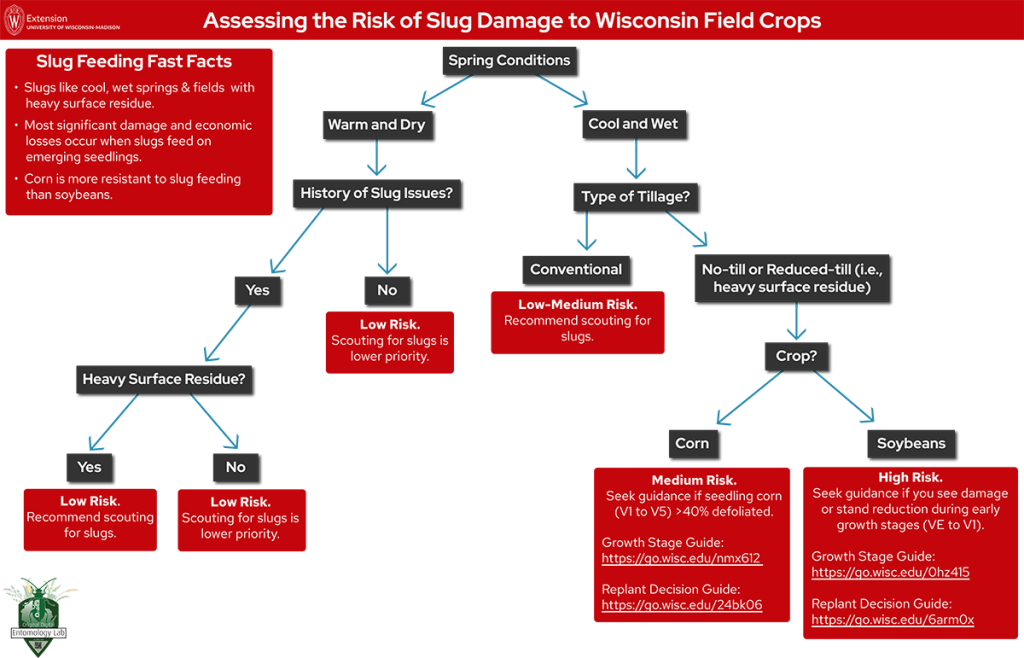

Developing a statewide slug monitoring program could help refine guidelines for Wisconsin and provide information on slug emergence, population densities, outbreaks, and general risk across the state. The risk assessment tree below can be used to assess the risk of slug damage to Wisconsin field crops.

Integrated pest management (IPM) strategies for slugs

Management of slugs can be more challenging than controlling most insects and weeds. Several pest management tactics in concert are typically needed to decrease slug populations and their damage over time.

Cultural

Older plants are less susceptible to slug-feeding damage compared to younger plants. Tactics that get plants growing as quickly as possible can potentially allow the crop to outrun and outgrow slug damage1. For example, early planting may allow for significant crop growth before slug eggs hatch or juveniles begin heavy feeding. Crop varieties with good emergence and seedling vigor can allow for better early growth. Pop-up fertilizers at planting could also enable quicker crop emergence and growth. Using row cleaners on planters to move residue away from the row will dry out the soil and allow more sunlight to penetrate. This creates an unfavorable habitat for slugs and can also increase soil temperatures and improve crop germination and growth. Planting early won’t eliminate slugs but can give plants a head start to get the crops past danger. In some cases, changing the planned crop to corn from soybean, if the rotation allows for it, may mitigate early slug damage in highly susceptible fields due to corn’s growing point being below ground until around the V5-V6 stage. In contrast, later planting when the soil is dry and warm can allow for quicker germination and growth of the crop when the slugs are already active. The choice to plant early or late will depend on the region, the suitability of soil for planting, and the timing of slug activity and crop planting dates.

Avoid planting susceptible crops in wet fields with heavy soil, especially ones that have had slug problems in the past. Ensuring seed slots are closed at planting can help prevent slug damage. Other practices to consider include diversifying crop rotations6, improving soil drainage, and providing slugs with an alternative food source at the time of planting (e.g., living cover crops)7.

Tillage is the most effective management tactic against slugs; this is contrary to the production practices and soil health benefits of no and reduced-till agriculture and, therefore, may not be a viable option for many farmers. However, strategies that minimize surface residue, like shallow disking or vertical tillage (2-4 in deep), will decrease slug damage but may not eliminate slug populations1,8.

Biological

Ground beetles, toads, garter snakes, and birds all prey on slugs and keep their populations in check. Ground beetles appear to be the most significant arthropod predator of slugs in crop fields1. Using methods to increase the number of these natural predators, such as using no-till and cover crops to attract beetles, can lead to effective biological control. If you are already using insecticides, be mindful to do spot treatments so as not to reduce beneficial insect populations. Avoiding insecticidal seed treatments (e.g., neonicotinoids) can help promote ground beetle populations and slug biocontrol in field crops9.

Chemical

Insecticides will not be effective against slugs because they are not insects. Instead, look for a molluscicidal bait when facing severe infestations and need a rescue treatment. Refer to A3646, Pest Management in Wisconsin Crops, by following this link for slug molluscicide recommendations in corn (Pg. 74). Metaldehyde-based baits (e.g., Deadline products) are not registered for use on soybeans in Wisconsin. This is not obvious because you must read a footnote on the label which indicates approved states. Iron phosphate products (e.g., Sluggo or Ferroxx AQ) are another option for field crops. Sluggo is listed for use in organic production.

The chemical arsenal for slugs is limited and baits are typically not a consistent standalone control method. They are relatively expensive, can be difficult to evenly dispense over the field, and can be ineffective if it rains (check the weather when planning a rescue treatment). Use molluscicides in the evening when slugs are the most active. It is more economical to spot-treat problem areas compared to treating a whole field.

When using pesticides, the label is the law. Read and follow directions and safety precautions on labels. Refer to A3646, Pest Management in Wisconsin Crops, for molluscicide recommendations.

Slug response and management options

If damage is not lethal, crops have most of the growing season to recover from slug damage1. Soybean stand reductions can be concerning, and farmers should decide if replanting is necessary given their specific conditions. See the following resource for detailed information to help guide any soybean replant decisions: Soybean Plant Stands: Is Replanting Necessary? If replanting is warranted, remember to scout the field and look for signs of damage because slugs will remain in the field and may feed on newly planted seedlings if conditions allow.

Apply molluscicides according to label instructions. Consider factors such as application method, rate, and pre-harvest intervals. Consider alternative management practices in severely infested fields (see cultural control section).

Consistent use of cultural practices, encouraging biological control, and judicious use of molluscicides and insecticides are the best ways to decrease slug populations over time.

Environmental and ecological considerations for slug treatment

Slugs tend to be most damaging when crops are being established and during early growth in the spring and fall. They can be serious pests of field crops in no-till and reduced till systems that leave residue on the surface and have little soil disturbance. The stable, cool, and moist microclimate under residue favors slug activity and development. Slug populations are expected to be large and problematic during a wet spring following a mild winter, or any spring after a wet fall.

Minimize pesticide use whenever possible to reduce potential impacts on non-target organisms and environmental health. Molluscicide baits, especially metaldehyde-based baits, can be ineffective if rain is forecast. Neonicotinoid seed treatments are known to harm ground beetle populations and reduce their effectiveness as biological control agents of slugs9. Implement IPM practices that promote biological diversity and ecosystem resilience.

Questions about slugs in conservation cropping systems? Contact Dane Elmquist (dane.elmquist@wisc.edu)

Additional Resources

For assistance with slug management and other agricultural pest issues, contact your local agricultural extension office or entomology expert.

References

1. Douglas, M.R., Tooker, J.F. 2012. Slug (Mollusca: Agriolimacidae, Arionidae) Ecology and Management in No-Till Field Crops, With an Emphasis on the mid-Atlantic Region. Journal of Integrated Pest Management. 3 (1): C1-C9.

2. Raudenbush, A.L., Pekarcik, A.J., Haden, V.R., Tilmon, K.J. 2022. Evaluation of Slug Refuge Traps in a Soybean Reduced-Tillage Cover Crop System. Insects. 12(1), 62.

3. Pennsylvania Slug Monitoring Project. https://extension.psu.edu/2024-pennsylvania-slug-monitoring-project

4. Ohio Slug Monitoring Project. https://agcrops.osu.edu/newsletter/corn-newsletter/2024-22/slug-monitoring-project-summary

5. Goh, K.S., Gibson, R.L., Specker, D.R. 2004. Gray Garden Slug. Field Crops Fact Sheet No. 102GFS795.00. Cornell Cooperative Extension. Cornell University.

6. Busch, A.K., Douglas, M.R., Malcom, G.M., Karsten, H.D., Tooker, J.F. 2020. A high-diversity/IPM cropping system fosters beneficial arthropod populations, limits invertebrate pests, and produces competitive maize yields. Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment. 292 (15): 106812.

7.LeGall, M. Boucher, M. Tooker, J.F. 2022. Planted-green cover crops in maize/soybean rotations confer stronger bottom-up than top-down control of slugs. Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment. 334(15): 107980.

8. Lefever, A.M., Wallace, J.M., White, C.M., Duiker, S.W., Esker, P.D., Tooker, J. 2024. Vertical tillage effects on crop production and pest management in Pennsylvania. Agronomy Journal. 116: 520-530.

9. Douglas, M.R., Rohr, J.R., Tooker, J.F. 2015. Neonicotinoid insecticide travels through a soil food chain, disrupting biological control of non-target pests and decreasing soya bean yield. Journal of Applied Ecology. 52(1): 250-260.

Updated: April 21, 2025

Reviewed by PJ Leisch, Extension Entomologist and Director of the Insect Diagnostic Lab

First crop insect scouting in alfalfa

First crop insect scouting in alfalfa Early season insect scouting in soybean

Early season insect scouting in soybean Early season insect scouting in corn

Early season insect scouting in corn ▶ Considerations for 2026 Seed Selection

▶ Considerations for 2026 Seed Selection